Interfaith Insight - 2024

Permanent link for "Pursuit of Happiness as a Quest for Virtue," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on March 12, 2024

Thomas Jefferson wrote to the head of a boarding school who had requested “a moral morsel” to be shared with the students as something they “should keep ever in their eye.” Jefferson emphasized the wisdom of Cicero in his response: “If the Wise, be the happy man, as these sages say, he must be virtuous too; for, without virtue, happiness cannot be."

The founders of our nation, including Jefferson and others who drafted the Declaration of Independence, understood “the pursuit of Happiness” differently than we do today. The famous sentence, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness,” was more aspirational than descriptive. It certainly was not true for those held in slavery, and it wouldn’t become true for women’s right to vote for over another one hundred years.

Jeffrey Rosen, president of the National Constitution Center, published this year his book, The Pursuit of Happiness. He discusses how happiness has changed its meaning since our nation’s founders, who were very influenced by Cicero and classical writers, and who saw the pursuit of inner happiness as a pursuit of virtue rather than the mere feeling of happiness.

Jefferson along with John Adams and Benjamin Franklin, who were also on the committee drafting the Declaration, were well-read in the classics including Cicero, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius. Their writings on the pursuit of virtue were influential and framed the founders’ understanding of pursuing happiness. Classical moral philosophy was studied by them and was an important part of the curriculum until the mid-1900s. Happiness was framed in terms of being good rather than feeling good.

The classical understanding of the pursuit of happiness is summed up by Rosen as “being a lifelong learner, with a commitment to practicing the daily habits that lead to character improvement, self-mastery, flourishing, and growth. … Happiness is always something to be pursued rather than obtained — a quest rather than a destination.” He quotes Cicero: “The mere search for higher happiness, not merely its actual attainment, is a prize beyond all human wealth or honor or physical pleasure.”

Rosen writes that happiness does not come from controlling external events, but from a focus on controlling “our own thoughts, desires, emotions, and actions.” He relates this to the Eastern wisdom traditions of Buddhism and Hinduism. John Adams found great interest in discovering that Pythagoras, one of the founders of Greek moral philosophy, in his travels to the East studied with Hindu masters. For our nation’s founders, pursuing happiness included reading from the wisdom traditions of the East and the West, and the texts of the Bible.

Cicero wrote over 2,000 years ago but significantly influenced our nation’s founders. He also wrote that “Gratitude is not only the greatest of the virtues, but the parent of all of the others.” Today the science of positive psychology is learning the power of gratitude and its relationship to happiness. The Insight referenced last week pointed to many of these studies as well as to the influence of the world’s religions.

Whether we understand it through the science that studies the virtues, or the impact of the classical writers on our nation’s founders, or realize it as a part of our religious beliefs, gratitude and the pursuit of the virtues are fundamental to true happiness and living a life with meaning.

Permanent link for "Seeing Others As Persons With Ultimate Worth," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 26, 2024

Originally published July 12, 2018

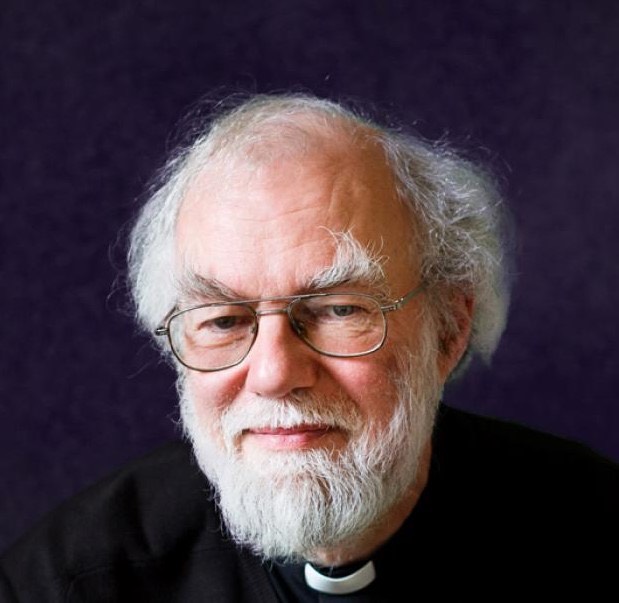

The Rev. Dr. Rowan Williams for 10 years served as the Archbishop of Canterbury and head of the worldwide Anglican community. He is now the master of Magdalene College at Cambridge University and someone I look forward to hearing and speaking with each time I return. His latest book, Being Human ,” explores what it means to be human in terms of body, mind, and personhood.

In his chapter, “What is a person?” he makes the distinction between being an individual and being a person. Anything can be an individual instance of a certain category of things. I have a Model T and it is an example of something called an antique car. I can list the characteristics that establish it as a car and as an antique. There are distinctions between antique and vintage cars, or classic cars. The various states define antique differently when one is seeking an antique or historical car registration or license plate.

But when it comes to being a person, is there a checklist that one can list to determine whether one is a person, or is there something irreducible about being aperson? For Williams, description doesn’t work. We must go beyond the bundle of facts to define what it means to be a person. He writes:

“We can never say, for example, that such and such a person has the full set of required characteristics for being a human person and therefore deserves our respect, and that such and such another individual doesn’t have the full set and therefore doesn’t deserve our respect.” There is something irreducible, not just a fact about me, but “something mysterious, something not open to third-person analysis.”

The key is relationship, Williams argues. “We sense that our environment is created by a relation with other persons, we create an environment for them, and in that exchange – that mutuality – we discover what ‘person’ means.”

For Williams this has a profound religious basis, the assumption that “before anything or anyone is in relation with anything or anyone else, it’s in relation to God.” Thus, “when I look around, my neighbor is also always somebody who is already in a relation with God before they’re in relation with me. That means that there’s a very serious limit on my freedom to make of my neighbor what I choose, because, to put it very bluntly, they don’t belong to me.”

Williams warns about the individualist approach that looks to the self as the center, and not the relationships. In our world today he sees “an evolution of an ‘uncooperative self’ – a self that assumes that what comes first is this isolated interior core which then negotiates its way around relations with others … away from a sense of belonging with each other and taking responsibility for each other.” Quoting the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville, he writes, “Each person, withdrawn into himself behaves as though he is a stranger to the destiny of all the others.”

If I take the individualist approach I am tempted to see others not as persons in their own right, already in relationship, but as objects to be used or useful to my individual ambitions or desires. One is then inclined to respect others only when they share the same characteristics as oneself. Do they look like me, talk like me, come from the same racial and socioeconomic status, worship like me? Can I tick off enough on my checklist to respect them as human, like me?

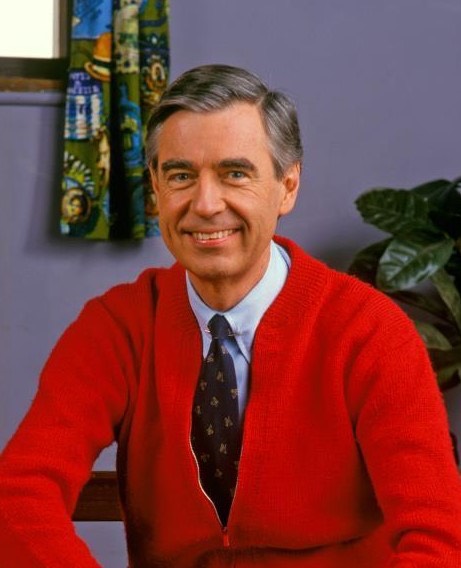

Returning from Cambridge, I’m struck by the interest in Mr. Rogers and his neighborhood. The documentary playing in theaters has generated multiple glowing reviews and essays. What is it about his story that draws our attention? I believe that in our individualistic, depersonalized climate, it is almost a revelation that there is another way to live. Rogers treated everybody, especially the children he spoke to and loved, as persons. They were not just individuals to be analyzed and checked off to determine if they merited respect. They were persons respected precisely because of their being – respected regardless of race, background, or physical limitations.

In a current essay, New York Times columnist David Brooks tells of a time when Fred Rogers met a 14-year-old boy who had cerebral palsy and asked the boy to pray for him. The boy, who had himself been prayed for many times, was shocked that Mr. Rogers requested his prayers. Later a reporter complimented Rogers on his clever way to boost the boy’s spirit by requesting that the boy pray for him. Rogers’ response was immediate. “Oh, heavens no, I didn’t ask him for his prayers for him; I asked for me. I asked him because I think that anyone who has gone through challenges like that must be very close to God. I asked him because I wanted his intercession.”

Brooks continues, “And here is the radicalism that infused that show: that the child is closer to God than the adult; that the sick are closer than the healthy; that the poor are closer than the rich and the marginalized closer than the celebrated.”

Rogers treated every person, every child with whom he interacted, as persons with inestimable value. Each person loved first by God deserved his love and respect as well. Let us follow his example and treat each person with the respect deserved, as one made in God’s image and loved first by God.

Permanent link for "Interfaith, Truth, and Social Justice," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 19, 2024

Originally published May 10, 2018

One of the persons I look forward to seeing and hearing in Cambridge is the former Archbishop of Canterbury, the Rev. Rowan Williams. Author of over 35 books, Lord Williams is also an academic and is currently the Master of Magdalene College. He spoke this week at the Woolf Institute on the topic, “The Importance of Interfaith for Social Justice,” and preached the sermon at Evensong at Magdalene College this past Sunday.

Most crises are not local. In the environment, political world, economic, or health arenas, issues cross national and faith community lines. Hence, our response cannot just be local. Underlying each of these concerns is the question, “What is it to be fully human?” Williams spoke directly about this in terms of the migrant issue in the United Kingdom. What do we owe to another person as a human being, but not necessarily a citizen? The faith communities must respond together on these issues.

Williams spoke of a common crisis that creates a common challenge, which must be met with common compassion. When the faith communities go beyond understanding and dialogue to working together for the common good, then action becomes the face of the interfaith efforts. He also turned the title around to explore “The Importance of Social Justice to Interfaith.” When we see someone who is “the other” involved in acts of generosity and compassion, we see the humanity in them and appreciate the depth of human character. It is a transformation in our “looking.”

He referred to the great American Catholic social activist Dorothy Day as one who lived her faith through her action in caring for the poor. He called it a “healthy counter to too much theology.”

In his book, Faith in the Public Square , Williams discusses the related issue of religious diversity and social unity. Does working together for the common good imply that we ignore our differences? Do we give up our truth claims in order to accept those who believe differently? He is critical of what he calls the “hopeful fantasy” that talking about truth is less important than talking about social harmony and justice.

Williams argues that the disagreement about truth among faith communities is actually very important to our common life. In the absence of making truth claims we leave open the door for power to have the last word. When we make claims for transcendent values, we must recognize that others also make such claims.

Williams writes, “What is needed for our convictions to flourish is bound up with what is needed for the convictions of other groups to flourish. We learn that we can best defend ourselves by defending others. … Christians secure their religious liberty by advocacy for the liberty of Muslims or Jews to have the same right to be heard.”

Thus our mission is not to give up our truth claims in order to seek justice, but to work with others “in finding what sort of values and priorities can claim the widest ownership.”

It is also a recognition that for most of our history the values of society have been shaped by religious belief. As Williams put it, “Diversity of faith points us towards a past in which there is a kaleidoscope of human perceptions, sometimes interacting fruitfully, sometimes in profound tension. … Religious diversity becomes a stimulus to find what it is that can be brought together in constructing a new and more inclusive history.”

This is true not only among religious traditions, but also within any particular community. We grow not by having everybody be alike, but by learning from each other. Whether it be in a denomination, a congregation, a family, or even a business, it is diversity that brings growth and new insight.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, previous chief rabbi for Great Britain, expressed this well in his influential book, The Dignity of Difference . Earlier solutions to difference led to crusades and the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants in the 1700s. Seeking to assert or defend a particular religious position through violence is also behind many of the terrorist acts of today.

Why do some people hate the ways that others worship God? Perhaps our concept of God is too small. If we took God seriously, Sacks suggests, we might see that God is bigger than our religions. He warns, “In a century when our powers of destruction have grown so great, either we live together or, God forbid, we die together.”

Religion must be a part of the solution, or it will continue to be a significant part of the problem. Williams again warns against the “compromise of fundamental beliefs or that the issue of truth is a matter of indifference. … But there is a proper humility which, even as we proclaim our conviction of truth … obliges us to acknowledge with respect the depth and richness of another’s devotion and obedience to what they have received as truth.”

In this attitude of respect, we recognize that “none of us have received the whole truth as God knows it; we all have things to learn.” Furthermore, our passionate beliefs as Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhist, Sikhs or whatever else, are received as a gift not an accomplishment.

Affirming truth in a spirit of humility enables us to respect that others also affirm truth. Through dialogue and by working together we can find ways to support the common good and resist recourse to power and violence. It is in this way that we expand our understanding of God’s truth and work together for social justice and peace.

Permanent link for "Maintaining One's Identity While Learning From Others," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 13, 2024

Originally published April 11, 2019

The challenge for America is to embrace an ethic that includes “respect for different identities, relationships between diverse communities, and a commitment to the common good.”

This is the theme of Eboo Patel’s book, Out of Many Faiths: Religious Diversity and the American Promise . We have discussed his recounting of the origins of religious freedom in America’s founding. From the attitudes and statements of our founders to the provisions in our Constitution, America was founded on principles that endorsed freedom of religion and prohibited religious tests for holding public office.

The question is not only how does our nation carry forward these founding principles to make room for all religious expression, but also how does a particular religious community “embrace the nation’s common life while maintaining its difference.” Patel is clear that response is not the “melting pot” image, often used to describe how we come together. That assumes we are somehow absorbed into a common mix that obliterates our differences. He prefers the image of a “potluck” where we bring our various dishes to share and where the variety enhances our experience with mutually different experiences.

An important part of this manner of coming together is sharing our stories in ways that enable us to learn from each other as well as learn with each other. Patel shares some of his personal experiences as he learned to appreciate his own heritage while also learning from others.

He tells of when he was in junior high and very self-conscious of his minority status. When his grandmother from India attended one of his junior high functions “at my largely white suburban school, dressed in her Indian clothes and speaking with her Indian accent, I quaked with embarrassment.”

One of his teachers, sensing his situation, told him that his grandmother reminded her of her Italian grandmother. She continued, “Outside of native peoples, we all come from somewhere, and we should take pride in our heritage and customs of our family.” Patel recounts how this made him feel more fully American.

He also recounts the story of how his father came from India to America. Patel explains, “I am in this country because an institution started by French priests in the Indiana countryside in the 1840s, committed to the faith formation and economic uplift of poor Midwestern Catholic boys, somehow saw fit to admit a wayward Ismaili Muslim student from Bombay into its MBA program, in the 1970s. That man was my father.”

Patel continues to describe his father’s devotion to Notre Dame’s Fighting Irish football team, leading to the occasion of what he identifies as one of his earliest interfaith memories. Frequent trips on Football Saturdays from Chicago to the campus always included a stop at the Grotto, a shrine to the Virgin Mary. On one occasion, Patel quizzed his father about why he as a Muslim would pray at a shrine dedicated to a Christian figure. His father pointed to the hundreds of candles and quoted from the Qur’an that God should be seen as “Light upon Light.” He then said, “You have a choice whenever you encounter something from another tradition, Eboo. You can look for the difference, or you can find resonances. I advise you to find the resonances.”

Many years later as Patel told of his experience, he was encouraged to share it with Father Theodore Hesburgh, who for over 50 years had served as president of Notre Dame and built the university into a major global institution “all the while maintaining its Catholic identity.” Patel and his Catholic friend Gabe were later invited to meet Father Hesburgh, then in his 90s, to hear his story. Patel noted the “growing number of Muslim, Evangelical, and Jewish faculty, staff, and board members at the university,” and asked Hesburgh how he dealt with the “traditionalists” who might not have been happy with the growing diversity.

Hesburgh noted the difference between Catholic with a large C, which stood for a particular institution, and catholic with the small c, which meant “universal.” He then explained, “We have to understand our Catholic tradition in a way that helps us accomplish our catholic mission, which is to lift up the well-being of all.”

As they were getting ready to leave, Patel’s Catholic friend Gabe asked for a blessing. Father Hesburgh “then motioned for me to kneel and close my eyes as well. It was, for my friend, a Catholic ritual of great significance. For me, it was an American sacrament.”

Is it possible that as we learn more about, and with, those of different faith traditions, that we too can “look for the resonances”? Can we even find ways to participate in each other’s special practices in ways that bring us to further understanding rather than promoting ways to confront and divide? It may not be easy but our identities might actually be enhanced and strengthened as we relate deeply to others while working for the common good.

Permanent link for "Refugees Tell Their Inspiring Stories of Hope," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 6, 2024

Originally published in 2018

Clementine Sikiri arrived in the USA in 2003 from a refugee camp in Rwanda. At 9 years old, she started learning English and eventually went on to major in English and Elementary Education at Grand Valley State University. Just a year ago, following a terrible accident, when her car was hit by a cement truck, she spent weeks at Mercy Health Saint Mary’sHospital and months in physical therapy. She will tell her refugee story at this year’s Abrahamic Dinner next Tuesday, Feb. 11, along with two other refugees.

For her first nine years, Clementine lived in awful conditions of war-torn Rwanda, then in a refugee camp, before coming to a strange land and having to learn a new language. For some time while living in the camp with her father and grandmother, they did not know where her mother and two siblings were. It was a great relief when her mother and one of the siblings were reunited with the family. Her oldest brother had been taken away to fight in the war and they did not discover that he was alive until much later after the family came to America.

The process of being approved as a refugee takes a long time, and it was such a relief when they were finally approved. She says that even when approved they had no idea where they would be sent, but anyplace outside of the camp was called “America.” Actually, some were sent to Europe, but they were so happy when they came directly to Grand Rapids on June 23, 2003. The large airport in Chicago and the huge buildings were quite impressive. Her mother was nine months pregnant and gave birth three days after their arrival in Grand Rapids.

Managing life after their arrival, without knowing the language, was quite difficult at first, but Clementine gives much credit to neighbors and others who helped them as they struggled to settle. They loved the house since it had a toilet, carpet, and a fridge. She describes the contrast to her earlier years living with no electricity, no running water, and having to search the forest to find wood for their stove.

They didn’t know anyone when they arrived, and in an interview she describes: “It was really hard because we didn’t speak English, and it was really frustrating sitting in that class when you didn’t know what the teacher was saying, everybody looks different, and nobody understands you.”

She praised the mentors in her life that helped her adjust and succeed. She cites individuals who told her how things work, about making connections, getting scholarships and finding jobs. “I'm so grateful,” Clementine says. “Ever since I got here I've always felt supported by Americans.”

She did survive, and did quite well, graduating from high school and then pursuing college at GVSU. She was excited when after high school she got a job at the YMCA working in the Child Development Center. She was so excited that she could get a job, especially one working with kids. As she shared, “The kids loved me and my bosses were really nice. I discovered that I really like kids. So when I worked there I decided to teach.” She finished her studies, graduated from GVSU, and then took a job as a refugee resettlement care manager at Bethany Christian Services.

In a recent article she explained, “I’m very passionate about helping people who come here as refugees – who come here with nothing – to become independent and self-sufficient. It brings me joy to help them create a life here, just like my family did.”

But life took an unfortunate turn a year ago when, driving home from visiting a friend, her car was hit by a cement truck in an accident that nearly took her life. A posting by Mary Free Bed Hospital described her condition:

“The impact was so great it caused her skull to separate from her spinal column, internally decapitating her. She was taken to Mercy Health Saint Mary’s Hospital, where doctors worked to save her. Clementine’s injuries were life-threatening. In addition to her spinal column, Clementine experienced a moderately severe traumatic brain injury, her leg and jaw were broken, and she had a stroke during surgery that caused temporary paralysis.”

Clementine recounts, “My doctor told me it’s a miracle I survived. I’ve always known that life is a beautiful gift from God and should be cherished each day that you’re blessed with it.”

Her rehabilitation took over seven surgeries and many weeks of therapy to regain strength and mobility. “But I know I’m lucky,” she says. “I was given the biggest gift – a second chance at life. There’s no reason for me to be angry.”

Dr. Stuart Yablon, medical director of Mary Free Bed’s Brain Injury Program, described the medical issues, complications and setbacks, as well as the immense support of her family and the community. He reflected, “Hers is not a medical story as much as a human story. It’s a story of perseverance and grace, of family sticking together during tough times.”

Clementine made such good progress that she was cleared to graduate last April from the inpatient program and continue with outpatient therapy for the next few months. She says, “Life can be taken from you in seconds. You can just exist, or you can live a rich, meaningful life. Life is so precious, and we aren’t promised tomorrow. Just love.”

Clementine Sikiri shared her refugee story at this year’s Abrahamic Dinner on Feb. 11, 2018

Our country is deeply enriched by individuals who for one reason or another had to leave their home and start a life here. Their journeys and stories may be quite different, but in each there is hope.

Permanent link for "What One Chooses To Forget, A Warning," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on January 30, 2024

“One can tell a great deal about a country by what it chooses to remember…. One can tell even more by what a nation chooses to forget.” These are the words of Lonnie G. Bunch III, the founding director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and currently head of the entire Smithsonian Institution, the world’s largest collection of museums and research and education efforts. Writing in a recent issue of The Atlantic, Bunch expands the theme of what we choose to forget, “what memories are erased and what aspects of [a nation’s] past are feared. This unwillingness to understand, accept, and embrace an accurate history, shaped by scholarship, reflects an unease with ambiguity and nuance—and with truth…. Why should anyone fear a history that asks a country to live up to its highest ideals—to ‘make good to us the promises in your Constitution,’ as Frederick Douglass put it? But too often, we are indeed fearful. State legislatures have passed laws restricting the teaching of critical race theory, preventing educators from discussing a history that ‘might make our children feel guilty’ about the actions and attitudes of their ancestors. Librarians around the nation feel the chilling effects of book bans.”

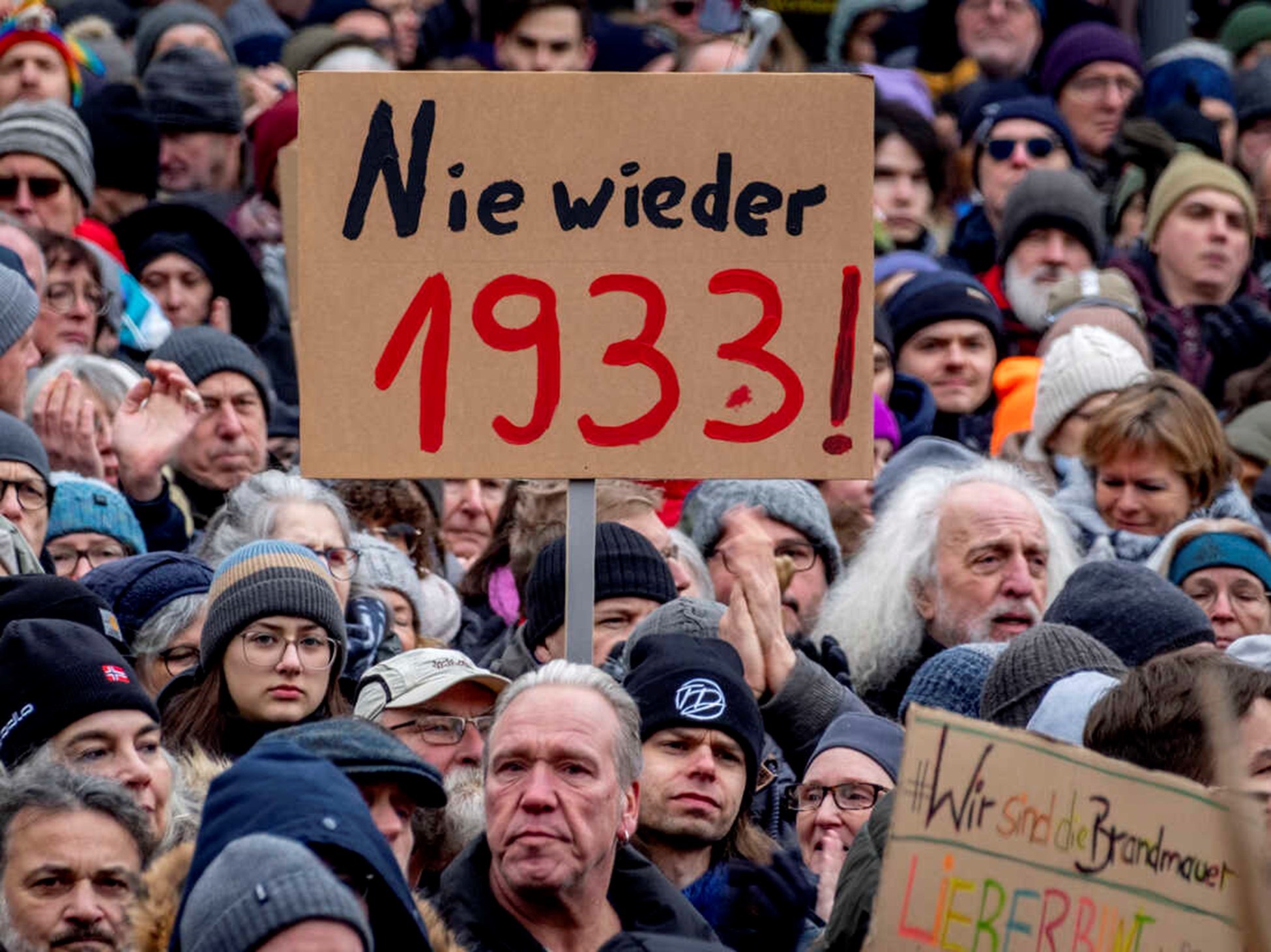

Some of you know that our eldest daughter married a German pastor, and we have four dual citizen grandchildren. In Germany they do the opposite, systematically remembering the lessons of the Nazi period and the horrors of the holocaust. It is against the law to produce, distribute or display Nazi symbols or swastikas. The march in Charlottesville of neo-Nazis displaying with swastika flags was shocking and unthinkable to German citizens. Holocaust denial is illegal, and the lessons of the past are to be remembered lest we further hate and extremism.

These lessons are so ingrained in the German public that just last week hundreds of thousands demonstrated against right-wing extremism throughout the country. Responding to an investigative news report of extremists meeting to explore mass deportations of people of foreign origin, protests in Berlin, Munich, Cologne, Hamburg, Frankfort, and many other cities drew thousands. Carrying signs like “Against Hate,” “Defend Democracy,” “Nie wieder 1933!” (“Never again 1933!”), the protestors, most of whom were not even born then, were reminded of that fateful year when in January 1933, Hitler was elected Chancellor. By March of that year the Dachau Concentration Camp was established, in April 1933 the law was passed excluding Jews and other political opponents from holding civil service or any government positions. In that year there was also a national boycott of Jewish-owned business, book burning of “un-German” books throughout the country, and laws mandating forced sterilization of persons with physical and mental disabilities.

In his effort to bring government and religion together, Hitler supported the German Reich Church also formed in 1933. While he cynically supported this effort to combine church and state, Hitler was no believer but used this effort to consolidate his power and as a way to silence dissenters.

There was an effort to combat this misuse of the church by Lutheran pastor Martin Niemöller who sent out a letter to pastors to come together in 1933 in the formation of the Pastors’ Emergency League. This led to a gathering of clergy and lay, meeting in May of 1934 where the Confessing Church was established. From this meeting came the Barmen Declaration, written primarily by Karl Barth, which became the rallying document to oppose the German Reich Church. The Barman Declaration affirmed Scripture and rejected the false teaching of the German Reich Church that supported Hitler’s attempt to bring church and state together under his leadership.

Niemöller was arrested by the Gestapo in 1937 for his opposition and spent the next seven years in concentration camps including Dachau before being freed by Allied forces at the end of the war. Niemöller is also remembered for this quote:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak

out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade

unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade

unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak

out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was

no one left to speak for me.

Other theologians and pastors in the Confessing Church were active in opposing Hitler, among whom was Dietrich Bonhoeffer who was arrested and put to death late in the war. His writings have been widely influential and his book The Cost of Discipleship is considered a modern classic.

The importance of religious leaders standing against political attempts to manipulate church and other communities to achieve their power cannot be ignored. Even Albert Einstein, not known for his strong faith, recognized the importance of those whose faith requires them to call out false ideas. He said, “Only the church stood squarely across the path of Hitler’s campaign for suppressing the truth….I am forced to confess that what I once despised, I now praise unreservedly.”

Do the religious communities in our own day, as well as others who seek truth, have the commitment to learn from mistakes of the past, and to stand and speak out for what is right?

Permanent link for "Finding Meaning: The Various Paths We Take," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on January 22, 2024

Originally published August 1, 2019

Why have many prominent people found faith and reported mystical experiences while in prison?

David Brooks writes about some of these in his book, The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life . When he discusses the first mountain, it is about ambition, strategy, and independence. It is about making your own way in the world, becoming independent from family, building a career, seeking to make a mark in the world. But when life’s circumstances put one in prison the ability to pursue these goals is radically eliminated. That first mountain now seems impossible.

Brooks writes about Anwar Sadat, who was imprisoned during World War II and later became the president of Egypt. Writing about the loss of his material things and his freedom, Sadat describes his transcending “the confines of time and place. … I felt I had stepped into a vaster and more beautiful world and my capacity for endurance redoubled.” He writes of his individual entity merging into “the vaster entity of all existence, my point of departure became love of home (Egypt), love of all being, love of God.”

Václav Havel, author, playwright, and public intellectual, was a political dissident during the Communist era. Following the country’s liberation he became president of Czechoslovakia and then served for over ten years as president of the Czech Republic. He describes his rejection of the materialist basis of the Marxist philosophy and his affirmation of spiritual reality. He writes, “The salvation of this human world lies nowhere else than in the human heart, in the human power to reflect, in human modesty, in human responsibility.”

While in prison and very sick, even near death, Havel writes in a letter to his wife about a “dizzying sensation of tumbling endlessly into the abyss … an unending joy at being alive, at having been given the chance to live through all I have lived through, and at the fact that everything has a deep and obvious meaning.”

Brooks also writes about the experiences of Viktor Frankl as a prisoner in the Nazi concentration camps. Frankl saw his condition as more than just a physical struggle but also a spiritual one. Frankl writes, “The way in which a man accepts his fate and all the suffering it entails, the way in which he takes up his cross, gives him ample opportunity – even under the most difficult circumstances – to add a deeper meaning to his life.” Frankl famously describes “the last of the human freedoms – to choose one’s attitude in any given circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Soviet dissident Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn in prison wrote, “Bless you, prison. Bless you for being in my life. For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul.” Brooks describes him as being given “a sense of participation in a larger story.”

For Brooks this larger story is the key to meaning. He writes, “Of what story or stories do I find myself a part? If there are no overarching stories, then life is meaningless.” But he goes on to affirm that “life does not feel meaningless” and it is these stories that “provide the horizon of meaning in which we live our lives – not just our individual lives, but our lives together.” Brooks finds the Exodus story as forming Jewish life and belief. He observes, “God commands Moses to tell the story of the liberation before He actually performs the liberation.”

Brooks describes his own coming to the realization of faith while hiking up to American Lake, which is a high mountain lake near Aspen, Colorado. While sitting on a rock overlooking the lake he pulled out a book of prayers he had taken with him, one of which is titled, “The Valley of Vision.” He reads the first line, “Lord, high and holy, meek and lowly” and observes the mountain peaks as well as the small animals nearby. As he reads on, “Where I live in the depths but see Thee in the heights,” he realizes what he calls the “whole inverse logic of faith. The broken heart is the healed heart. The contrite spirit is the rejoicing spirit.”

He then describes the “sensation of things clicking into place … a sensation of deep harmony and membership. … Life is not just a random collection of molecules that happen to have come together in space. Our lives play out within a certain moral order.” Brooks denies this experience as some kind of religious conversion, but “more like a deeper understanding … seeing the presence of the sacred in the realities of the everyday.” While in his valley of personal struggle and seeking meaning, he described some who tried to convert him as some “sort of win for their team” as not at all helpful but a kind of “destructive force.” He advises those who seek to help someone in the “middle of any sort of intellectual or spiritual journey: Don’t try to lead or influence. Let them be led by that which is summoning them.”

Following his hike to American Lake, Brooks says he realized that he was a religious person. As he explains, “To be religious, as I understand it, is to perceive reality through a sacred lens, to feel that there are spiritual realities in physical, imminent things.” He quotes writer and Trappist monk Thomas Merton: “Trying to see God is like trying to see your own eyeballs.” Brooks then explains that God is “what you see and feel with and through.”

Brooks’ book about seeking the second mountain is very candid and self-disclosing. For some reviewers it is too much, but I have learned from his transparency and willingness to share his journey. Each of our journeys toward meaning takes its own path. It is important not expect another person to have the same experience as one’s own, but to respect, learn, and rejoice in the variety of ways we find meaning in our lives.

Doug Kindschi

Permanent link for "Reflections in the new year" by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on January 9, 2024

These have been difficult times for interfaith discussions given the intensity of the conflict in the Middle East. It is hard to know how to respond. To be supportive of either side greatly offends the other side given the polarized positions. Even being critical is either not critical enough or not understanding the issue, depending on which side one stands. Not taking a position is interpreted as a moral failing, again depending on where one’s loyalties are.

While it is highly unlikely that any position taken locally will have any impact on the geopolitical crisis, what is clear is that we must do all we can to work to prevent it becoming a faith conflict. We must work even harder to keep it from developing into Antisemitism and Islamophobia. This is our mission as the Kaufman Interfaith Institute.

On many campuses, it has happened that the conflict has turned into faith conflicts and hate against persons who have a particular faith identity or commitment. Hundreds of synagogues and Jewish organizations have received bomb threats and physical damage as well as defaced building. Violence and threats have also been received as well by Muslim places of worship and by individuals. This even led to the violent killing of a young Muslim boy in Chicago. Individuals and facilities in these faith communities are under threat and must take extraordinary procedures to preserve safety.

These conditions will never contribute to resolution in the Middle East, but will only lead to increased conflict, hate, and even violence locally.

A friend and Muslim, who has worked for years on campuses and in Israel for peace between the religious communities, recently reported that three of his former Israeli Jewish students were killed by Hamas during the raid on October 7 and shortly thereafter five of his Muslim colleagues were killed in Israel’s retaliation in Gaza. The loss of innocent life on all sides is tragic and very personal for many. We must grieve with them while also doing what we can to see that this violence does not extend to hate and violence against faith groups in our own communities.

Religion News Service recently published an opinion essay by Baptist minister and president of the Interfaith Alliance, The Rev. Paul Brandeis Raushenbush. He urged faith communities not to retreat, but to work even harder to maintain our interfaith commitment to understanding and meaningful relationships. He writes:

“Those of us who work to bring understanding among people of diverse faith traditions, no matter our own faith, are horrified to to see the religious tapestry that makes up American democracy begin to fray and tear apart. Having worked for interfaith cooperation for almost three decades, I have never experienced a more challenging and heartbreaking time.

“Yet inaction and retreat are not the answer. I have never been more convinced that we can, and we must, continue to be in relationship with one another. We can feel passionately that our own views on the crisis are just, even as we acknowledge that others may have very different views. We must acknowledge the pain people are feeling on all sides and acknowledge the humanity of people we disagree with.”

That is our commitment at the Kaufman Interfaith Institute during this time of international challenge. Let us all commit to dialogue, understanding, and developing relationships, even if we have deeply differing views on how to resolve this tragic conflict.

Shalom, Salaam, Peace.

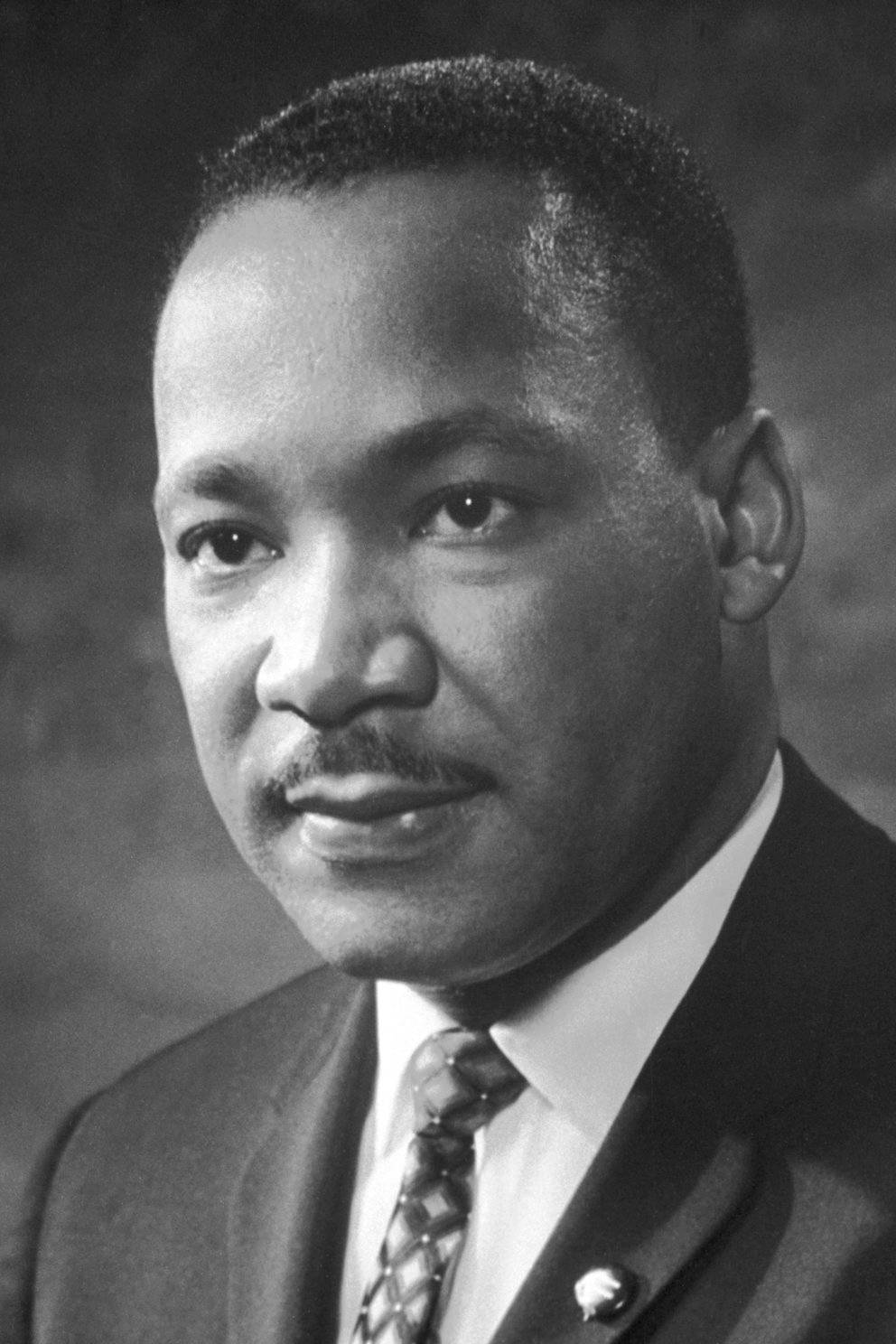

Permanent link for "Martin Luther King, Jr., Seeking justice through love" by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on January 22, 2019

Originally published in 2019

"Let Justice roll down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

This quote from the Hebrew prophet Amos, was a favorite used by Martin Luther King, Jr. in his famous “I Have a Dream” speech in August, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C.

This past weekend we again remember him for his commitment to non-violence and his leadership in the civil rights movement. He was fond of quoting Amos and the other prophets as he saw his own efforts as similar to the Jewish struggle for freedom from slavery in Egypt.

He used the quote earlier in his Letter from a Birmingham Jail in April of 1963. One year prior to his death, he spoke to over 3,000 in Riverside Church in New York City when his concern for justice expanded to the cause of peace in view of the carnage of the Viet Nam war. He concluded his speech with, “If we will but make the right choice, we will be able to speed up the day, all over America and all over the world, when justice will roll down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

In his final speech, the evening before he was assassinated, we again hear the prophet’s words calling for justice. King ends by evoking the image of the Exodus and Moses seeing the Promised Land while not actually getting there. He concludes, Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land!”

The Muslim leader, Eboo Patel, founder and president of the Interfaith Youth Core, finds inspiration in the life of King, a Christian who in turn was inspired by the Hindu Gandhi. Patel points out that King did not reject Gandhi because he was of a different religion but instead “sought to find resonances between Gandhi’s Hinduism and his own interpretation of Christianity. King referred to Gandhi as “the first person in history to lift the love ethic of Jesus above mere interaction between individuals to a powerful and effective social force.”

The cause of justice goes beyond racial division to include also religious division. Some would see religious diversity as a cause for prejudice and even hatred. Just as King reached out to Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel and Buddhist Thich Nhat Hanh, we cannot afford to let religious differences create separation and exclusion and even violence. Patel paraphrases one of King’s principles, “the world is not divided between black and white or Christian and Muslim, but between those who would live together as brothers and those who would perish together as fools.”

In a recent publication King’s prayers, we read the following:

“O God, we thank you for the fact that you have inspired men and women in all nations and in all cultures. We call you different names: some call you Allah; some call you Elohim; some call you Jehovah; some call you Brahma; some call you the Unmoved Mover. But we know that these are all names for one and the same God. Grant that we will follow you and become so committed to your way and your kingdom that we will be able to establish in our lives and in this world a brother and sisterhood, that we will be able to establish here a kingdom of understanding, where men and women will live together as brothers and sisters and respect the dignity and worth of every human being. In the name and spirit of Jesus. Amen."

In his talk at Riverside Church, King called for a revolution of values leading to a loyalty to all of humanity. One that “lifts neighborly concern beyond one's tribe, race, class, and nation. He called for an “embracing and unconditional love for all mankind.” By love, he did not mean some sentimental effort but a “force which all of the great religions have seen as the supreme unifying principle of life.” He called this love “the key that unlocks the door which leads to ultimate reality.”

He went on to refer to the “Hindu-Muslim-Christian-Jewish-Buddhist belief about ultimate” that was summed up in the New Testament epistle of John, “Let us love one another, because love is from God; everyone who loves is born of God and knows God. Whoever does not love does not know God, for God is love.” (I John 4:7-8)

King admonishes, “We can no longer afford to worship the god of hate or bow before the altar of retaliation. The oceans of history are made turbulent by the ever-rising tides of hate. And history is cluttered with the wreckage of nations and individuals that pursued this self-defeating path of hate.”

In King’s speech upon receiving the Noble Prize for Peace in 1964, he told of a famous novelist who had died. Among his papers was a list of suggested story plots including one where a widely separated family inherits a beautiful mansion, but on the condition that they have to live together. King continues:

“This is the great new problem of mankind. We have inherited a big house, a great ‘world house’ in which we have to live together – black and white, Easterners and Westerners, Gentiles and Jews, Catholics and Protestants, Muslim and Hindu, a family unduly separated in ideas, culture, and interests who, because we can never again live without each other, must learn, somehow, in this one big world, to live with each other.”

Let us live out King’s commitment to racial and religious unity as we seek to remember his example and teaching about the power of love reinforced by the deep values in all of our religious traditions.