Interfaith Insight - 2024

Permanent link for "Finding Truth In Great Literature; Will We Make the Right Choice?" by Douglas Kindschi, Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVS on June 4, 2024

Originally published August 13th 2015

Inspiration for my weekly Interfaith Insights usually comes from my reading non-fiction, but this column is an exception. On the recommendation of my orthopedic surgeon, this summer I read John Steinbeck’s classic, East of Eden .

So what does this novel have to do with interfaith? This retelling of the Genesis story is also the story of the conflict between good and evil and the struggle that is within each of us. The main character, Adam, discusses with his friend Samuel, and his servant Lee, possible names for his twin boys. They read the story of the biblical Adam’s two sons, Cain and Abel. They are at first bothered by Cain’s violent response to the rejection of his plant offering while Abel’s animal offering was accepted.

Lee comments: “I think this is the best known story in the world because it is everybody’s story. I think it is the symbol story of the human soul. … I think everyone in the world to a large or small extent has felt rejection. And with rejection comes anger, and with anger some kind of crime in revenge for the rejection. … There is the story of mankind.”

This passage reminds me of the alienation that some members in our society must feel when they find that they just don’t fit in, that they have been rejected because of racial difference or religious difference. For most this rejection is somehow overcome, but for others the rejection leads to anger and violent response. It is a sad commentary but perhaps, as Lee expressed, “the symbol story of the human soul.”

The discussion between Adam and his friends continues with puzzlement over the passage where the Lord responds to Cain’s anger that his offering is not accepted. The passage reads: “So the Lord said to Cain, ‘Why are you angry? And why has your countenance fallen? If you do well, will you not be accepted? And if you do not do well, sin lies at the door. And its desire is for you, but you should rule over it.” (Gen. 4:6-7)

Lee later discovers other translations of the passage and pursues the key passage by studying Hebrew with other learned men, including a respected rabbi. The key word that was translated “you should” rule over sin, is in Hebrew the word “timshel,” and can also be translated “thou mayest” or “you can” rule over sin. It is not a command but the recognition of human free will to resist the sin. It is a choice!

Friend Samuel exclaims, “Thou mayest, Thou mayest! What glory! It is true that we are weak and sick and quarrelsome, but if that is all we ever were, we would, millenniums ago, have disappeared from the face of the earth.” But we are given choice, we can choose to win over sin.

Later in the book, Steinbeck returns to what he calls the “one world story.”

“Humans are caught — in their lives, in their thoughts, in their hungers and ambitions, in their avarice and cruelty, and in their kindness and generosity too — in a net of good and evil. … Virtue and vice were warp and woof of our first consciousness, and they will be the fabric of our last. … There is no other story. A man, after he has brushed off the dust and chips of his life, will have left only the hard, clean questions: Was it good or was it evil? Have I done well — or ill?”

It all hinges on the single Hebrew word, “timshel,” “Thou mayest.” We have the choice. It is there in the early stories in Genesis. It is in great literature of the 20th century. It is with us today. It faces us as individuals, as nations, and in our attitudes toward others who are not like us. How will we respond to the sin at our door? Will we make the right choices?

Permanent link for "Into the Heart of Islam," by Kelly James Clark, Author and Former Kaufman Interfaith Institute Staff on May 28, 2024

I remember the first time I flew into Istanbul. Passing over the old city, formerly known as Constantinople, I saw massive mosques. The Fatih Mosque, construction completed in 1470 AD, displays the magnificence and solemnity expected of an edifice named in honor of Mehmet the Conqueror, the Ottoman sultan who conquered Constantinople in 1453. Its location, on the burial grounds of Roman Emperor Constantine, made a religious and political statement about God’s favor shifting from the Holy Roman Empire to the Islamic Ottoman empire; God, the Conqueror’s inspired architects were saying, is on our side. The indomitable Fatih Mosque seems more castle than cathedral.

Next in view: Suleymaniye, an imperial mosque commissioned by Suleiman the Magnificent, the tenth and longest-reigning Ottoman sultan (d. 1566).

As we approached the seaside, I saw the Hagia Sofia, first built in 537 by Emperor Justinian I as the official cathedral center of the Holy Roman Church. The Hagia Sofia was converted into a mosque by Mehmet the Conqueror in 1453. By destroying or plastering over the Christian art and icons and redecorating with Islamic symbols, the Conqueror was stating that God’s heavenly power and authority are now aligned with his/Islam’s earthly power and authority.

Again, these mosques seem more castle than cathedral.

This flyover, given a little bit of Wikipedia history, played into my anti-Muslim bias that Islam was at heart a conquering religion, which advanced more by the coercive power of the sword than the attractive power of righteousness and mercy.

The Blue Mosque, neighbor of the Hagia Sofia, is a dazzling masterpiece, of a decidedly different nature from the monuments to power. While constructed by Sultan Ahmet I as an assertion of Ottoman power, its cool and serene interior—20,000 handmade blue tiles with over fifty different tulip designs—is more an invitation to peace than an anthem to war. While only the Sultan was allowed to enter the mosque on horseback, the chains at the door forced the Sultan to bow in humility before Allah. As you enter, you remove your shoes, bow in humility, and, as your eyes adjust to the lack of sun, sense serenity and peace.

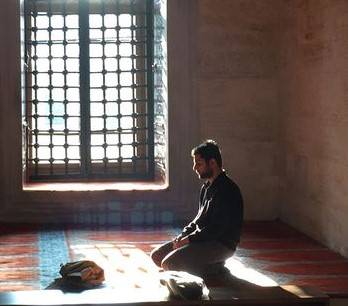

I had secured permission from Istanbul’s Grand Mufti to film a Friday prayer service, a privilege typically denied to non-Muslims. Since the Friday prayers constitute Islam’s pre-eminent form of public worship, the Blue Mosque was packed, with an undulating sea of thousands of people hip-to-hip in neatly spaced rows. In response to a series of calls in Arabic, everyone folded hands, bowed, kneeled, touched their foreheads to the ground, and stood up again in remarkable unison. Since I was not filming, I found myself standing, embarrassed, in the sea of these very prostrate worshippers.

Given the serenity of the Blue Mosque, the attraction of true devotion, the wafting Arabic, and the power of synchronized activity, I found myself strangely moved to pray with these strangers. So, discretely glancing to my left and to my right for cues and clues, I folded my hands, bowed, knelt, touched my forehead to the ground, and stood up again in passable unison. Inside the Blue Mosque, surrounded by thousands of strangers, acting in unison and in response to the lilting recitation of a sacred text, I felt, for the first time, the attraction of Islam.

I had once thought that Muslim rituals were empty and rote, that Muslims were just concerned with impressing God with the quantity of their prayers and the position of their bodies. But, as I spoke with the Muslim participants, I learned that, like Christians, Muslims are more concerned about a faithful heart than a prostrate body. And I felt the compassion contained in countless repetitions of love:

In the Name of Allah, the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful.

Praise be to Allah, Lord of the Universe,

the Most Compassionate, the Most Merciful!

I’ve taken you from the exterior of Islam into the heart of a Muslim. We started the journey with fortress-like mosques, reinforcing my bias that Islam is a conquering, not a peaceful, religion. I then took you inside a mosque, a place of peaceful architectural repose. Inside that mosque, I reported on the synchronous ritual behavior of thousands of people, behavior that invited me in. Finally, I shared a conversation I had with Muslims about how bowing and scraping conduce to humility, righteousness, and mercy.

I offered repeated iterations of exterior-into-interior, taking you from mosques to bodies and, finally, into hearts of love.

Permanent link for "Triennial Year Theme: Bridging Generations," by Karen Meyers, Kaufman Associate and Director Emeritus, GVSU Regional Math/Science Center on May 21, 2024

Since its inception, the Kaufman Interfaith Institute has maintained a practice of creating a triennial theme every three years. This tradition began with the Year of Interfaith Understanding and was followed by the Year of Interfaith Service, Year of Interfaith Friendship, and the Year of Interfaith Healing; each idea guiding the work of the Institute while engaging the community in the formation of practices that build relationships. And this year 2024, being a Kaufman Triennial Year, has a theme as well: the Year of Bridging Generations.

The concept of being a “bridge builder” is a strong one in the work of those involved with the Kaufman Institute. There are many stories of bridges that have been built over the years by the staff and volunteers of the Institute; work that, while challenging. is ongoing and fruitful in our community.

Something I have been thinking about as we hear stories of this work is the nature of bridge building. It is such a rich analogy of what we are being called to do. I began to picture in my mind all the different kinds of bridges and what it takes to build them.

- Some are long – some are short.

- Some are simple – some are complex.

- They are made of different materials.

- Some cross a small stream – some span a chasm.

- Some are impromptu – like when you are hiking in the woods and find a log to place over stream so you can cross. Others take a great deal of time, hard work (even teamwork), and planning to complete like the Mackinac Bridge (I'm from Michigan).

And, as bridges age, there may be a need to revisit their construction and provide for repairs in their structure. Or, as we have all seen recently with the Francis Scott Key bridge or with the collapse of the Tacoma bridge in 1940, bridges can be destroyed by catastrophic events and need to be rebuilt.

Our call in this time and place is to build the bridges necessary to span the generations. Recently, I have been made aware of the necessity to reflect on the connection between multiple generations - both past and future - that this relationship is necessary if we are to address the concerns of our community. This means that, if the work of interfaith is to continue, there must be links between the young and older; a reminder of the past as well as planning to extend our reach and collective wisdom in a way that will persist into the future. The torch must be passed as we continue the work.

In other words, we need to become bridge builders. On a day-to-day basis, there may be those small, simple, impromptu bridges that we can construct. Other bridges may take some planning and persistence so we may only have the energy to work on one of those bridges at a time. There are bridges that connect individuals and then there are bridges that connect organizations; bridges that allow us to cross over to understand those of different faiths and perspectives.

Already this academic year, the Kaufman Institute has become more deeply involved in this work of bridging the generations through an expanded outreach to the GVSU community, the interfaith scholars program, Interfaith photovoice, and more. In the coming weeks, we will be sharing this work with you. As I write this, it is my hope that you will reflect on how you might become a bridge builder. What interactions in your day-to-day life provide you with opportunities to connect with other generations, instilling in them the need for interfaith interactions in our community - locally, nationally and globally?

Permanent link for "Remembering previous evil as well as heroic deeds" BY DOUGLAS KINDSCHI, SYLVIA AND RICHARD FOUNDING DIRECTOR, KAUFMAN INTERFAITH INSTITUTE, GVSU on May 13, 2024

Originally Published 2018

Much has been written about the fact that a country like Germany, which was predominantly Christian, engaged in the horrendous events around the Holocaust. While we can blame Hitler and the government of the Third Reich, the fact remains that thousands of ordinary citizens in that country and surrounding countries participated in or at least watched the genocide being carried out.

The Catholic Church has been a target for complicity during that time, but there are many examples of individuals who have dedicated their lives to a type of repentance through their actions in seeking truth and telling the stories of “Never Forget.” I recall a few decades ago visiting Auschwitz and meeting a young German Catholic priest who had dedicated his life to living near that death camp and telling the story of the atrocities committed there.

A few years ago, we heard from the FrenchCatholic priest, Father Patrick Desbois, who also devoted his life to researching the stories of what he calls the “Hidden Holocaust” in Eastern Europe during World War II. For over two decades he has tracked down the sites of hidden graves and interviewed witnesses who describe the horrors of more than 70 years ago, when a total of more than a million Jews, babies, children, men, women, and elderly were shot and buried in unmarked ditches throughout Eastern Europe. His research has identified more than 2,000 such execution sites.

In 2004 he created the international organization Yahad-In-Unum (“Together as One”) with support from the Vatican and praise from Pope Francis. His research and important efforts are documented in his book, The Holocaust by Bullets: A Priest's Journey to Uncover the Truth Behind the Murder of 1.5 Million Jews .

Thanks to efforts by the Jewish Federation of Grand Rapids, the Diocese of Grand Rapids, the Catholic Information Center, and other co-sponsors including the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, Father Desbois spoke in Grand Rapids at the Catholic Information Center in 2018.

Another story on the same topic is told by Abdullah Antepli, thefirst imam at Duke University and Muslim leader whose chapter, “Never Again: A Muslim Visits the Nazi Death Camps,” appears in the book, My Neighbor’s Faith: Stories of Interreligious Encounter, Growth, and Transformation .” He tells of his trip along with a small group of American Muslims to four Nazi concentration camps in Germany and Poland.

Antepli writes, “The trip came as an unexpected answer to many years of personal prayer. As a recovering anti-Semite, who is deeply pained by current Jewish-Muslim relations … I knew I needed to develop a deeper understanding of the Shoah and its impact on several generations of Jews. As an imam and chaplain working actively to help heal the wounds between Jews and Muslims, I had to open myself more to the pain of my Jewish brothers and sisters.”

While he says that he has read books and seen films about the Holocaust, it was much more powerful to visit the actual sites and to “actually walk in the footsteps of millions of brutalized and murdered people.” He reflected on “all the people who participated directly and indirectly in this demonic campaign to exterminate the Jewish people and others considered marginal and unworthy of humane treatment.”

Antepli also shares the official statement that came from the group of imams who participated in this visitation. It begins with a quote from the Qur’an, “O you who believe, stand up firmly for justice as witnesses to Almighty God.” (4:135) The statement continues, “In Islam, the destruction of one innocent life is like the destruction of the whole of humanity and the saving of one life is like the saving of the whole of humanity.” (Qur’an 5:32) While bearing witness to the millions who perished fromsuch senseless and cruel murder, the statement also recognizes that many Muslims did heroic acts in protecting and saving the lives of Jews.

Yad Vashem, the Holocaust Remembrance Center in Jerusalem, recognizes many from Europe who risked their lives to help protect those persons persecuted. Their program, “Righteous Among the Nations” honors non-Jews who risked their lives to save Jews during the holocaust, including Muslims from Albania, Bosnia, Macedonia, Turkey, and Eastern Europe, who acted heroically at the time. While there has not been much publicity about these “Righteous Muslims,” their stories need to be told.

In Skopje, Macedonia, while the city was under German control, Dr. Todo Hadzi-Mitkov sheltered the Jewish Mois Frances and his family. When the conditions became more dangerous, they arranged false papers showing the Frances family to be Muslim and then taken by horse and cart out of Skopje to Albania, where they stayed with another Muslim family until Skopje was liberated.

In Bosnia, among the Muslim Righteous, the Hardaga family sheltered the Jewish Kavilo family when the Nazi forces occupied that area. In an interesting turn of events 50 years later, during the Bosnian Civil War, the Kavilo family was instrumental in getting permission for the Hardaga family to travel to Israel and escape the continuous bombing of Sarajevo.

These stories of Jewish-Muslim friendships and life-saving actions are now threatened by the emerging narrative that the two religions are at odds. We must also remember and celebrate the actions taken, often at great risk, to save the lives of those with whom we do not share a religious tradition. We need to remember our common humanity and do what is right for all persons made in God’s image.

Permanent link for "Israel and Gaza: Is there a better way?" by Douglas Kindschi, Sylvia and Richard Founding Director, Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on May 7, 2024

The violence and death of innocents continues in the Middle East. Over 1,200 Israelis were killed, and hundreds taken hostage by Hamas on October 7. The response from Israel has led to over 34,500 Palestinians killed in the retaliation.

Here in the U.S., many are responding in the form of protests, advocacy, education, and donating to humanitarian causes. At the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, our priority, in our West Michigan community and on our Grand Valley State Universitycampus, is to prevent and counter Antisemitism, Islamophobia, and other related forms of religious-based that are surging across our country because of this geopolitical conflict. This continues to be our approach and our highest priority.

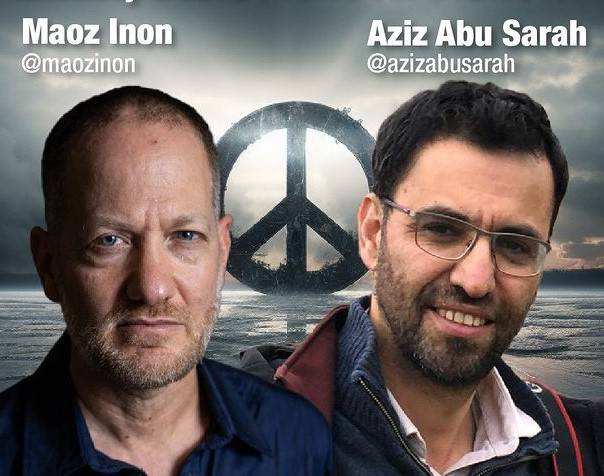

Yet, we are not alone in pursuing empathy and understanding amid this crisis. Others have undertaken a similar approach in response to this terrible suffering, the likes of which too often leads to more conflict and violence. One example involves someone who has been on our campus before. Aziz Abu Sarah is a Palestinian who grew up in East Jerusalem and experienced as a 9-year old child the capture of his older brother on suspicion of throwing rocks. His brother was arrested, beaten, and when finally released died from internal injuries to his body during the torture.

Aziz grew up with a hatred of Jews for the death of his brother, but later he decided to study Hebrew since that was the only way to get ahead in that culture. For the first time he met teachers and students who were Jews. They didn’t know his story and he didn’t know theirs. As he got to know them better he realized that the continual hatred on both sides was not the way to peace and justice. Revenge doesn’t lead to justice, just more hate. He decided it was his choice to find a different way. He and a new Jewish friend founded a travel company that puts Jewish and Palestinian guides together to explore and learn about both communities in that part of the world. You can learn his story in the short video at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L-4j-S3U5Fo&t=231s

Aziz recently became friends with another Israeli, Maoz Inon, who lost his parents and many childhood friends in the October 7 attack on the communities near the Gaza border. Aziz and Maoz had only met briefly once prior to the attack, but Maoz said that Aziz was one of the first to respond to him with condolence following the attack and thatcontact was important to him.

Aziz in turn responded with his surprise on how this Israeli was also grieving the death of so many Gazans. He said to Maoz, “you’re not only crying for your parents, you’re also crying for the people in Gaza who are losing their lives, and that you do not want what happened to you to be justifying anyone taking revenge. You do not want to justify war. And it's so hard to do that. So much easier to want revenge, to be angry.”

Aziz continues that he needed more time after his brother’s death from Israeli soldiers. He wanted revenge, and it was onlyyears later after getting to know Jews that he realized that could choose instead to find ways to partner in understanding difference and not be angry and hateful.

Maoz agrees, saying “that the first step in reaching a shared society and a shared future is knowing the other side's narrative. … And I learned so much in the recent months from speaking, dialoguing with Palestinians, I learned that we must forgive for the past. We must forgive for the present. But we cannot and should not forgive for the future.”

Aziz says heknows of countless victims in Gaza, including a friend who lost 50 members of his family. He responds to Maoz, “We are angry. I am very angry. Every time I read the newspaper, I'm angry. Every time I talk to one of my friends in Gaza, I am angry. But the thing is, I do not let anger, and we do not let anger, drown us in hate and wanting vengeance.

“People look at us and think we are divided because you’re Israeli and I’m Palestinian, Muslims and Jews,” he tells Maoz. “But if you must divide us, people should divide us as those of us who believe in justice, peace, and equality, and those who don’t — yet.”

You can watch the 17-minute Ted talk at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0juLRi90kRg

Let us all seek understanding instead of vengeance and work together for justice and peace.

Posted by Kyle Kooyers on Permanent link for "Israel and Gaza: Is there a better way?" by Douglas Kindschi, Sylvia and Richard Founding Director, Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on May 7, 2024.

Permanent link for "Can We Reject Fear And Find Hope In Spite Of The Evidence?," by Douglas Kindschi, Sylvia and Richard Founding Director, Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on April 15, 2024

Originally Published September 29, 2016

Can we find common ground or will our disagreements and fear drive us apart? Our recent event brought together Orthodox Jewish Rabbi Donniel Hartman with the first imam at Duke University and currently the Chief Representative for Muslim Affairs, Abdullah Antepli. “Can We Find Common Ground Between Israel and Palestine?” was co-sponsored by the Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies.

Our speakers acknowledged the conflict, suffering, fear, and violence that exists in that part of the world, but they choose to engage with each other on the issue and refuse to give up hope. The current efforts are not working and in fact create increased anti-Semitism and Islamophobia. The situation will not improve by continually blaming the other.

A driving force is fear, and fear takes on a life of its own. It starts with vilifying the one who wants to kill me or my children. Fear then leads me to vilifying people who might look like or have the same ethnicity or religion of the person I fear. Fear then begins to infect oneself. Fear leads to the abandonment of hope. We then are no longer willing to work for a solution.

Neither the rabbi nor the imam have given up hope. Even going against the grain of powerful forces, they publically engage each other and work together seeking to understand the other’s narrative and arguing for actions which do not destroy hope.

My own hope for the future received a boost last week at the meeting in Washington, D.C. of the President’s Interfaith and Community Service Campus Challenge. This effort, initiated by President Obama, now involves over 600 campuses throughout the United States who are committed to interfaith service in the community. Our next generation has hope, strengthened by their serving together in the community. One of our speakers was Eboo Patel, founder and president of the Interfaith Youth Core. As he did last year while speaking at three college campuses in Grand Rapids, Patel challenged us all with the vision of building a better world.

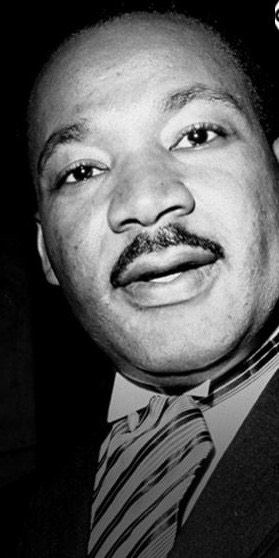

He reminded us of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech when he received the Noble Prize for Peace in 1964. King told of a famous novelist who had died. Among his papers was a list of suggested story plots including one where a widely separated family inherits a beautiful mansion, but on the condition that they have to live together. King then goes on:

“This is the great new problem of mankind. We have inherited a big house, a great ‘world house’ in which we have to live together – black and white, Easterners and Westerners, Gentiles and Jews, Catholics and Protestants, Muslim and Hindu, a family unduly separated in ideas, culture, and interests who, because we can never again live without each other, must learn, somehow, in this one big world, to live with each other.”

Our challenge is to maintain hope. This hope was expressed by our Jewish and Muslim speakers who are seeking common ground. It is the hope that motivates Eboo Patel and motivated King. And it is the hope that I see in the students who are inheriting our “world house.”

Author and activist Jim Wallis has famously said: “Hope is believing in spite of the evidence, and then watching the evidence change.” Let us join these leaders as well as the next generation in action that is motivated by hope and creates a world of peace.

Email: [email protected]

Permanent link for "Seeing the world not as a machine, but as a garden," by Douglas Kindschi, Sylvia and Richard Founding Director, Kaufman Interfaith Institute on April 9, 2024

Originally published on Sept. 7, 2017.

The recent solar eclipse caught the attention of nearly everyone as it made its path across the continental United States. While the total eclipse path was only 70 miles wide, millions traveled to that narrow strip to observe this phenomenon, which rarely covers so much of our country. As impressive as it was, I am also struck by our ability to predict with such precision the path as well as where and when it will happen again.

Our understanding of the solar system and its regularity has greatly increased since the work of the early astronomers and scientists such as Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and Newton. Their work led to the idea of a mechanical universe, highly regular and predictable. It even influenced our religious conception of God as an engineer who designed such a marvelous structure.

This image of God was greatly reinforced by the scientific developments of the 17th century with Newton and the mechanistic model for the universe. God the creator became God the engineer, the designer of the universe. As our scientific theories became more mathematical we had pictures of God the geometer. Scientists believed they were finding the mind of God as they discovered beautiful mathematical descriptions of the natural world. Even the artists pictured God with a compass laying out the world at creation. This mechanical model for the universe took hold as the predominate picture for the natural order. God was often seen as this engineer-creator: one who not only created the universe, but also created the laws by which this universe would run.

While this mechanical image of the universe may have made sense in a Newtonian world, it no longer works for a where quantum physics is based on indeterminate random events. It doesn’t fit an evolutionary biology based on random mutations and adaptation to changing environments.

Furthermore, it doesn’t even fit our theology of a God who desires good for us but does not take away our freedom and turn us into automatons. Control might not be the only or the best image for how God works in our lives and in our world. Perhaps we need to return to the biblical sources to rediscover the earlier images of a God who shepherds, who plants, who nurtures.

In the second creation story, found in Genesis 2, we see a God who plants a garden, causes trees to grow, and sees that they are watered. God forms Adam from the dust of the ground and breathes “into his nostrils the breath of life.” God walks in the garden in the cool of the day.

We see a different image of God, as a gardener who works with the earth to bring about life. Before I pursue this image further let me confess that I am not a gardener. But I am married to one and so I know a little about how gardening works.

First, a gardener doesn’t control every aspect of her creation. Plants do not always appear where and how it was intended. Sometimes a seed will be carried by the wind or a bird to a different place and the next year a plant will grow in a new location. Sometimes the root system gets too crowded and the plant needs to be dug up, separated and replanted as two or more plants. Weeds sprout up. Soil conditions and weather enter into the process. Some plants seem to have free will. No matter what you think you are intending, they just do their own thing. The gardener’s job is to nurture, shape and care.

Second, gardening takes time. Many years ago we put in a new pergola in our side yard and my wife planted the vines that would cover the structure. I thought it would give us the shade we had hoped for yet that year. It took six years for the vines to reach the top and begin to grow across the top. Now nearly 20 years later it provides a beautiful cover. Gardeners must be patient. Gardening has been described as the art form that requires the longest time to create. It takes hard work, constant effort, and most of all patience to shape and form the contours and colors desired.

Third, a garden is never finished; it is always in process. There is always more to do. It is a dynamic art form. It is not like painting a picture and at some point you are done. It is not like a poem that has a beginning and an end. It is not a symphony that can be heard in one night’s concert. It is always becoming, always being developed, always in process.

Do these characteristics of gardening describe God’s relationship to our world and even to our own lives? Do we understand God as one who nurtures and cares for us and for the creation? Does the working of God’s will often take time, more time than our impatient desires would expect? Is God’s work in the world and in our lives a work in progress, and not yet finished?

Permanent link for "Loving the Stranger in a Time of Oppression," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on April 2, 2024

Earlier version originally published on May 16, 2019

“Do not ill-treat a stranger or oppress him, for you were strangers in Egypt.” (Exodus 22:20)

In a time of increasing xenophobia and the normalization of hate talk, we need to be reminded of the religious call for not only love of neighbor but also love of the stranger.

We are familiar with the summary of the law given by Jesus when asked what must we do to inherit eternal life. He responded, “Love God and love your neighbor,” quoting the passage from the Hebrew Scriptures, "You shall love your neighbor as yourself" (Leviticus 19:18). That same chapter also deals with how to treat the stranger: “When a stranger lives with you in your land, do not mistreat him. The stranger living with you must be treated as one of your native-born. Love him as yourself, for you were strangers in Egypt. I am the Lord your God.” (Lev. 19:33-34)

The rabbis have counted over 30 references to loving the stranger in their scripture. In a column by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, former Chief Rabbi in the United Kingdom, he discusses two aspects of this command. “The first is the relative powerlessness of the stranger. He or she is not surrounded by family, friends, neighbors, a community of those ready to come to their defense. Therefore the Torah warns against wronging them because God has made Himself protector of those who have no one else to protect them.”

The second aspect is what Sacks calls the “psychological vulnerability of the stranger. […] The stranger is one who lives outside the normal securities of home and belonging. He or she is, or feels, alone -- and, throughout the Torah, God is especially sensitive to the sigh of the oppressed, the feelings of the rejected, the cry of the unheard. That is the emotive dimension of the command.”

Sacks writes that in the ancient world, “Hatred of the foreigner is the oldest of passions, going back to tribalism and the prehistory of civilization.” This is reflected in the story of Joseph when his brothers visit him in Egypt. When it came time to eat, the book of Genesis records, “They served him [Joseph] by himself, the brothers by themselves, and the Egyptians who ate with him by themselves, because Egyptians could not eat with Hebrews, for that is detestable to Egyptians.” (Gen. 43:32)

The dislike of those who seem different is an old phenomenon and often the source of racial and ethnic conflict. It is an increasing phenomenon in our own country as well as throughout the world. In times of uncertainty we often find comfort by affiliating with our own people, to those who look or think like we do, by returning to our separate tribes. All of our religious traditions, however, teach us to respect and provide help to the stranger.

Not only did the Torah teach that we should not ill-treat or oppress the stranger, but Jesus also tells of those who would be blessed because, “I was hungry and you gave me food, I was thirsty and you gave me drink, I was a stranger and you welcomed me. … Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brethren, you did it to me.” (Matthew 25:34-40)

The same can be found in the letter from the Apostle Paul to the Hebrews: “Let brotherly love continue. Do not neglect to show hospitality to strangers, for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.” (Hebrews 13:1-2) In addition, the letter from John says, “Beloved, you are acting faithfully in whatever you accomplish for the brethren, and especially when they are strangers.” (3 John 1:5)

We find similar admonishments in Islamic, Hindu and other religious texts. The Qur’an says, “Do good unto your parents, and near of kin, and unto orphans, and the needy, and the neighbor from among your own people, and the neighbor who is a stranger” (from Surah 4:36). In the Hindu tradition we read, “Let a person never turn away a stranger from his house, that is the rule. Therefore a man should, by all means, acquire much food, for good people say to the stranger: ‘There is enough food for you’” (from Taitiriya Upanishad 1.11.2).

The religious traditions promote this approach to caring for the stranger, but also studies show that diversity and inclusion lead to more vibrant communities.

The Jewish and Christian Scriptures recognize another reason to treat everyone with respect, with the concept of all persons being created in God’s image. Rabbi Sacks writes, “What is revolutionary in this declaration is not that a human being could be in the image of God. That is precisely how kings of Mesopotamian city-states and pharaohs of Egypt were regarded. They were seen as the representatives, the living images, of the gods. That is how they derived their authority. The Torah’s revolution is the statement that not some, but all, humans share this dignity. Regardless of class, color, culture, or creed, we are all in the image and likeness of God.”

In today’s environment, will we allow fear of the stranger, anti-Semitism, Islamophobia, and other types of hate-speech and even violence, to grow? Or, will we heed the lessons of our various faith traditions to respect all persons, love our neighbor and even the stranger? All persons of goodwill are called to affirm human dignity for all persons, especially the stranger.

Permanent link for "Appreciative Knowledge Helps Build Bridges," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on March 25, 2024

Earlier version originally published on March 15, 2018

“Americans are highly religious but have little content knowledge about religious traditions – their own or those of others.”

So wrote Stephen Prothero in his best-selling book Religious Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know – And Doesn’t. His recommendation was that more education about religion be taught in our schools from an objective perspective, “leaving it up to students to make judgments about the virtues and vices of any one religion, or of religion in general.” Hardly any school boards adopted his suggestion, and in many places the “objectivity” of the teacher would have been a significant issue.

Eboo Patel, founder and president of the Interfaith Youth Core, in his book, Interfaith Leadership takes issue with “just the basic understanding of other religions.” In the interfaith agenda we are not just dealing with abstract systems or textbook knowledge, he argues, “but actual people interacting in real-world situations.” He calls for an “appreciative knowledge” of other traditions, actively seeking out “the beautiful, the admirable, and the life-giving rather than the deficits, the problems, and the ugliness. It is an orientation that does not take its knowledge about other religions primarily from the evening news, recognizing that, by definition, the evening news reports only the bad stuff. … By being attuned to the inspiring dimensions of other religious traditions, such ugliness is properly contextualized.”

Patel’s whole approach is to build bridges between people and communities across religious lines. A beautiful example of such occurred in Grand Rapids when the Al-Tawheed Mosque and Islamic Center sponsored a “Know Your Muslim Neighbor Open House.” Hundreds attended and had the opportunity to visit the Prayer Hall, try on a Hijab, write their name in Arabic, and ask questions to refugees, teens, and women and men of this community.

A similar example occurred in the Jewish community when Temple Emanuel sponsored its “Taste of the Passover” with a light meal and a sampling of the traditions of the Passover Seder. It included holiday music and reading, an opportunity to ask questions and learn more about this important Jewish holiday.

Appreciative knowledge also involves the learning of important contributions to our current society and throughout history from the various religious traditions. How many of us know that the architect of the Sears Tower (now the Willis Tower) and the John Hancock Center in Chicago was a Muslim? Fazlur Rahman Khan, the architect known as “the Einstein of structural engineering,” was born in Bangladesh where he received his bachelor’s degree in engineering. He immigrated to the United States, where he pioneered a new structural design that initiated the renaissance in skyscraper construction during the second half of the 20th century.

Khan advised engineers never to lose sight of the bigger picture: “The technical man must not be lost in his own technology. He must be able to appreciate life, and life is art, drama, music, and most importantly, people.”

Mathematics also owes much to the preservation and innovation that came from the Muslim community especially from the House of Wisdom founded in the 8th Century in Baghdad. Our current Hindu-Arabic number system was introduced to the West from this center. Ever tried to multiply or do long division using Roman numerals? Many new techniques in solving equations came from the mathematician al-Khwarizimi, whose Latinized name became the term for algorithm. The word “algebra” came from one of the words, “al-jabr,” in the title of his famous book on solving equations.

The House of Wisdom was also where many of the Greek classic texts had been translated into Arabic and preserved. The West would likely not have many of the works of Plato, Aristotle, and Euclid, had it not been for the preservation of these texts by this major contribution of Islamic civilization. Appreciating these contributions also helps us understand how much we owe to other religious traditions.

Eboo Patel also discusses the Jewish author Chaim Potok and his novel The Chosen. It is the story of two Brooklyn orthodox Jewish boys, one whose father is a Hasidic rabbi; the other is more liberal and seeks to put his Jewish faith in conversation with the broader intellectual traditions of the modern world. While the fathers disagreed on many things, the more liberal father tells his son, “There is enough to dislike about Hasidism without exaggerating its faults.” It can be a very different position and we can disagree but “it ought to be appreciated as well.”

One of the challenges of interfaith dialogue is to learn how to disagree and yet have appreciative knowledge about other faith commitments. Interfaith is not a new belief system that says everyone is the same and we all essentially believe the same things. We have important differences, but we can still learn from each other and appreciate the values expressed through these different ways of understanding.

We are called to build bridges of cooperation across differences, and one of the important building blocks is this appreciative knowledge. Networks of engagement help create relationships among those who orient around religion differently. In this way we build understanding that can lead to new friendships.

Permanent link for "When Politics and Religion Mix in Unhealthy Ways," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on March 19, 2024

These are confusing times in the political world, both internationally and in our own country. Taking sides on geopolitical issues can often feed either Antisemitism or Islamophobia, or both. We have continued to address those issues here in West Michigan in ways that respect all persons’ religious understanding while also grieving the terrible killing of innocent civilians.

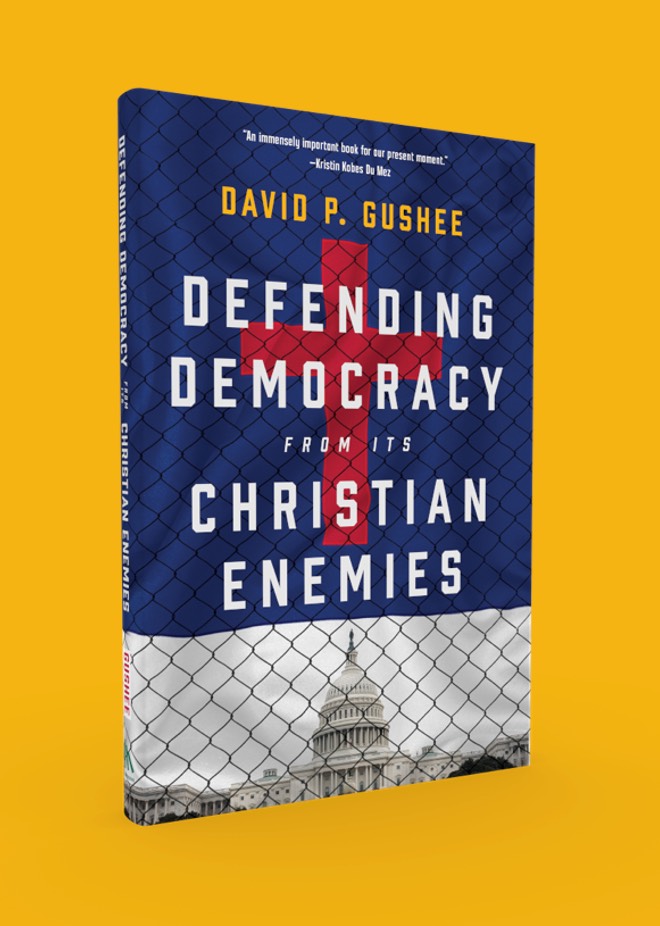

There are issues in our country as well as in parts of the world that show another danger when politics and religion interact in unhealthy ways. Last week Eerdmans Publishing and the Kaufman Interfaith Institute presented a program that exposed the danger of politics using religion in ways that are damaging to democracy and to sincere religious understanding.

Calvin University professor Kristin Kobes Du Mez, author of The New York Times bestselling book Jesus and John Wayne, interviewed David Gushee, author of the recent book, Defending Democracy from its Christian Enemies. Gushee writes that his book is one of Christian ethics, which offers a “vision for Christians in society that have democracy but are at risk of losing it.” He draws his vision from, in his words, “my reading of biblical prophetic tradition and the teachings of Jesus.” He also recognizes that this is not only a threat in America but also in other countries with different religious traditions.

Gushee begins his defense and analysis of democracy with a famous quote from the theologian Reinhold Niebuhr: “Man’s capacity for justice makes democracy possible, but man’s inclination to injustice make democracy necessary.” Democracy in its modern form was a reaction to centuries of monarchical absolutism and was expressed in the American and French revolutions of the 18th Century. It became marked by leaders being chosen by the people and civil rights and freedom being protected.

The world has experienced challenges to this democratic political system in the 20th Century, when it was perverted into autocratic rule by the right-wing movements in Italy under Mussolini and when the Nazis took power in Germany with Hitler. We are seeing beginnings of similar attempts in Turkey, Putin’s Russia, Poland, Orban’s Hungary, and Brazil. Gushee warns, “Unless there is a mechanism within a democracy for politicians demonstrating clear antidemocratic tendencies to be disqualified from standing for office, this vulnerability will always exist within democracy.”

Patriotism becomes “ultranationalism” when, Gushee warns, “the nation is identified with a particular ethnic, religious, or cultural group” that poses a threat to the interests and rights of other groups, as when Anti-Jewish ultranationalists in Nazi Germany identified Jews “as non-citizens, then as non-human, then as worthy of death.”

Looking more directly at the American scene, Gushee identifies a conservative coalition of Christians and nominal Christians whose rhetoric suggests “antisemitism, xenophobia, and patent racism, that is flat-out ethno-nationalism.” He clearly identifies the “special concern of this book is the role of Christians and Christianity in relation to all these negative trends.” He shows how Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” was for these followers a signal to restore white Christians to power in economic and cultural arenas, and a pushing back against societal trends “perceived as sinful or that unseated white Christians as the nation’s norm-setters in social change.”

In a section titled “Taking a Nation Back for God by Any Means Necessary,” Gushee summarizes the current political situation as follows: “Trump gained reactionary Christian support in large part because he sent every possible signal that he would wield his power relentlessly to achieve the religious counter-revolution that reactionary Christians have desired for so long."

Our nation has been served well by the democratic system, rule of law, and protection of rights for all citizens. Religious freedom has been protected and has not been seriously challenged for most of our history. When immigrants and people of minority religious identities are threatened, it is a dangerous development – especially when it comes from a perspective that even contemplates an attack on our Constitution.

[1716913435].jpg)