Grand Valley University Foundation History

It began with meager assets: $95, and that included $20 from one of its three founders to pay the incorporation fee. But, like the fledgling college it was created to support, the Grand Valley College Foundation was born with big dreams and high hopes.

With those dreams in mind, three West Michigan community leaders – Richard M. (Dick) Gillett, Keith R. Baker, and Philip W. (Phil) Buchen – gathered one summer day in 1963 to incorporate a nonprofit organization that would be officially chartered as a 501(c)(3) in 1965. The organization began with a single purpose; raising money to help build and support the college then rising in a rural area centrally located to serve Grand Rapids and the lakeshore. That first meeting took place a month before the college opened its doors to students for the first time.

Even before convening the foundation’s first meeting, Gillett, then executive vice-president of Old Kent Bank & Trust, had been instrumental in leading the Buck-a-Brick campaign and the effort to acquire land for the Allendale campus. He was the foundation’s first president. Baker, manager of First Michigan Bank in Allendale, agreed to serve as the foundation’s treasurer. Buchen, a former law partner of then-Congressman Gerald Ford, was the college’s vice president of business affairs. He became the foundation’s first secretary.

From the beginning, the three foundation officers – and those who succeeded them – recognized the importance of maintaining close ties to the college and the larger community. The foundation solidified the bond between the college and the community that continues to this day.

The foundation also forged a close relationship with the college administration beginning with James H. Zumberge, Grand Valley’s first president. That partnership has continued with his successors.

Early support for the Grand Valley College Foundation went beyond cash. The Albert Kraker family helped Grand Valley attain land for the Allendale campus. And, support from the Thomas E. Seidman Foundation helped put a down payment on a home in East Grand Rapids that would serve as the official residence for the college president.

“This idea of giving is so ingrained into the nature of Grand Valley,” said Arend D. (Don) Lubbers who became president in 1969 replacing Zumberge. Lubbers oversaw much of Grand Valley’s growth before retiring in 2001.

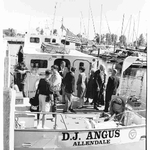

Other property gifts would help establish meaningful programs and traditions alive today and significant to Grand Valley. In 1965, the foundation accepted a yacht named for its owner D.J. Angus. The Angus became the first vessel operated by Grand Valley for the purpose of studying freshwater resources. The college also received gifts of art, including hand-signed prints by Alexander Calder, some of which became part of Grand Valley’s permanent collection. Private donations had helped build the Loutit Hall of Science, the first dormitories, the Seidman Student Center and Lubbers Stadium.

For its first decade and well into its second, the foundation had relatively little money in its accounts. But, the foundation directors were not discouraged. They were confident the community would continue to show its support.

Throughout the 1970s, the foundation officers who would help the foundation grow from its beginnings as an amorphous organization to one with more definition, intention, and purpose were Keith R. Baker, John S. Edison, Peter J. DeWitt II '68, Nancy M. Mulnix '95, and Peter J. Reed.

In 1974, realizing the foundation needed to find other funding sources, its directors supported a survey of leading citizens in Grand Rapids, Holland, Grand Haven, and Muskegon to assess the feasibility of expanding the foundation’s efforts by creating a more defined development effort to raise private funds. The additional funds were necessary to strengthen teaching, open doors for students with scholarships, and expand course offerings. The survey results clearly showed that the citizens would support this effort.

In 1976, the foundation held its first Enrichment Dinner to honor supporters and raise money for an endowment that would provide the margin of excellence in good times and maintain stability and quality in more difficult times.

Grand Valley, by then well-established in Allendale, recognized the growth taking place in downtown Grand Rapids. Foundation members helped President Lubbers and the college to identify the need for a downtown campus, seeing it as a way to provide greater access to the institution in the hub of the region’s business community by better connecting the student population with the region’s businesses for internships and jobs. And, it would allow the college to expand its graduate courses.

Grand Valley started teaching downtown in borrowed spaces and demand quickly outpaced available space. But a new campus would require levels of private philanthropy that were well beyond what the college had reached at that time. Grand Valley would need additional support from private foundations and hundreds of more individuals. The Grand Valley College Foundation would need to recruit more directors and the foundation board would need to become a cross-section of area leaders with the expertise to raise the needed funds.

The work was just beginning.

As the 1980s dawned, the Grand Valley College Foundation was reinvigorated with an expanded board of directors. Paul A. Johnson, a prominent Grand Haven industrialist and long-time college Board of Control member, agreed to serve as president and began to reorganize the foundation. He made it his mission to recruit the region’s finest talent and leadership from business and civic organizations. The foundation was at a crossroads, needing to grow in a time when access to funds was changing dramatically.

“Finding itself in a funding pinch at a time when it had just gained stature as one of the state’s leading colleges was an especially hard blow to Grand Valley,” Johnson said in the renewed foundation’s first annual report. “Somehow it didn’t seem fair. Grand Valley had fought too hard to get where it was, and it wasn’t going to be done in by a lack of dollars.”

The 1980s found much of the nation faced with a recession, and Michigan was no exception. Paul Johnson knew the task before him and the other foundation directors was challenging, but he expressed assurance that the West Michigan region would, once again, rise to the occasion. Johnson believed that Grand Valley President Arend Lubbers, the college, and its supporters had invested too much time and money to let it wither.

“The time has come for all of us to protect that investment so future generations of area citizens will have the opportunity to improve their skills in business, education, and public service,” said Johnson. He challenged the foundation leadership. “We have chosen to view this situation as an opportunity and to plan for the future in what we hope is a realistic way.”

The foundation directors unanimously approved a reorganization plan, bringing the foundation into a closer partnership with the college. The foundation would serve as a “citizens’ advisory body” to the college president and the Board of Control on all major educational projects requiring private funding. Joyce Hecht would become executive director of the foundation as well as director of the university’s development office. The foundation also voted to expand the foundation directors to include 30 “community leaders whose prestige and authority will encourage others to participate in an active relationship with the institution.”

Casey Wondergem, a Grand Rapids public relations executive and foundation director, agreed to lead the first membership drive, building a core of support from people who would make annual donations. The foundation and development office created a newsletter called Horizons for all donors and friends. The journey toward building a comprehensive, broad relationship and philanthropic partnership between the community and its college had gone to the next level.

By the early 1980s, Grand Valley’s endowment stood at $3 million. But that was far short of the amount needed to meet the college’s long-term needs.

Johnson, Lubbers, and the foundation’s directors set two formidable goals:

- By the end of the decade, the foundation should increase the college’s endowment to $10 million.

- In addition, the foundation should raise another $6.1 million to help build a planned campus in downtown Grand Rapids, the largest construction project in the foundation’s history. That effort was deemed the Grand Design campaign.

The foundation leadership agreed that a downtown Grand Rapids campus would put Grand Valley into the region’s population center, allowing it to meet the demand for graduate and undergraduate programs, particularly for working adults. The administrators and faculty also began planning for new programs in computer science, nursing, physical therapy, and facilities management, all of which would meet clear needs in the region’s growing economy but couldn’t be provided without the financial support from the foundation.

Jim Sebastian, a foundation director, proposed starting a school of engineering to meet a growing need by area businesses. He agreed to chair a “downtown committee” to begin to plan the Grand Rapids campus. In 1981, Grand Valley began by acquiring four acres on the west bank of the Grand River, all purchased with money that had been gifted.

By 1988, Grand Valley was able to open its first downtown building. The new building was named the L.V. Eberhard Center in recognition of supermarket entrepreneur L.V. Eberhard who gave $1.25 million. It also included the Meijer Public Broadcast Center named for another major donor, retail chain owner Fred Meijer.

The nine-story building was the first of many to be built downtown, and it included classrooms, a conference center, engineering labs, and a studio for the college’s public television station. At that same time, the foundation’s Grand Design campaign had exceeded its original $6.1 million goal, raising nearly $9 million from 4,100 donors.

By 1990, the foundation had made headway on its commitment to building the college’s endowment fund. It stood at $7.1 million with a significant portion of that money raised through the foundation’s annual Faculty and Staff campaign launched in 1981.

As Michigan Governor James Blanchard signed a bill designating Grand Valley as a university in recognition of the depth and breadth of its academic programs, the foundation renamed itself the Grand Valley University Foundation. The foundation board’s first move under its new name was to appoint a number of long-time supporters – William F. Beebe, Peter C. Cook, L.V. Eberhard, Richard M. Gillett, Robert Pew II, Edward Schalon, James Sebastian, Sr., and L. William Seidman – to what was called the Advisory Cabinet, the purpose of which was to recognize high levels of leadership and counsel the foundation.

The decade of the '80s became pivotal in the growth of Grand Valley, and the foundation was at the forefront of each new endeavor. The university’s Allendale campus needed a multi-denominational center for campus ministry and a life sciences building. In addition, foundation director and Amway Corporation co-founder Rich DeVos agreed to lead a fundraising campaign for Grand Valley’s Water Resources Institute that would help establish the university’s role in protecting the Great Lakes.

While most communities postponed fundraising efforts in the early 1980s in an effort to hold out for better economic times, the Grand Valley University Foundation had other ideas.

“The temptation to rest is enticing after prolonged effort and significant accomplishment,” Lubbers said in a 1988 speech. “Resting on laurels is heady stuff, but finally it is like a mental quicksand. Let’s keep our engines running. Let’s keep our enthusiasm for our quest…When we are enthusiastic, we make things happen that others thought impossible. We appear to work miracles. This foundation has done it before. Let’s keep doing it!”

The foundation’s achievements in the 1980s motivated business and civic leaders throughout the region to take Grand Valley State University to new heights as it entered a new decade. With enrollment increasing exponentially, a new campus emerging in the heart of the city, and the region retooling itself to compete in the changing economy, the Grand Valley University Foundation set even more-ambitious goals for itself in the 1990s. The foundation began to identify strategic ways that Grand Valley State University might help to shape the region’s new economies. At the top of the list of strategies was to forecast the jobs that would be needed in the future so the university could prepare the talent needed to fill those jobs.

“The urge is strong to consider issues of this decade that will persist into the next century,” foundation President Paul Johnson and Grand Valley President Don Lubbers wrote in a joint message to supporters. “The ability of our students to realize their hopes and expectations is the promise of tomorrow for Michigan – and particularly, perhaps, for West Michigan…This promise for the future, however, needs our active support.”

While planning for the future, the foundation saw many of the projects it had supported in the 1980s coming to fruition in the 1990s. The Cook-DeWitt Center, a multipurpose facility and recital hall for special events that was named for supporters Peter and Pat Cook and Marvin and Jerene DeWitt, was dedicated on the Allendale campus in November 1991. That project included the adjacent Cook Carillon tower, now a university icon.

The 1990s marked a milestone in the university’s history. Grand Valley had become the fastest growing institution of higher learning in Michigan thanks in large measure to those who supported the foundation. Still, the university and foundation knew there was more work ahead to keep pace with the needs of these students and the rapidly changing economy they would enter.

The new economy called for more jobs for engineers, scientists, and medical professionals, and the foundation was ready to help the university prepare students to fill those positions by providing money for the facilities and programs necessary for that purpose. The foundation raised funds for the university to host the National Science Olympiad’s national championship in 1998, to encourage youth to consider a career in the sciences. It also reached its goal of $5.1 million for the Water Resources Institute to study fresh water resources, which was later named the Robert B. Annis Water Resources Institute in Muskegon.

The foundation’s most ambitious effort to improve science education was its commitment to raise funds as part of the effort to establish a $41 million science complex on the Allendale campus. In addition, the Kresge Foundation offered a $500,000 challenge grant to equip the science labs if the foundation could raise another $1.5 million. Once again, the foundation’s supporters came through.

In 1991, foundation President Paul Johnson stepped down, and Rich DeVos became the new president of the foundation. As DeVos took the reins, he credited Johnson with setting in motion many projects that would continue into the next century.

DeVos immediately focused his attention on the downtown campus. Under his leadership, a group of 24 supporters called the “GVSU Land Barons” was formed to raise money and acquire acreage for expansion of the downtown campus beyond the footprint along the river with the Eberhard Center.

Like many projects before, the foundation’s vision of a comprehensive downtown campus was more than just ambitious; it was life-changing for the people of the region. This vision included facilities for graduate and professional education. It included classroom space for the Seidman College of Business, the College of Public Administration, a graduate library, business outreach centers, and other key programs.

Banker and philanthropist David G. Frey agreed to chair the downtown capital campaign, coined Grand Design 2000. The downtown campus would bring courses to “a new level of students, a new group that was untapped otherwise,” recalled Fred Meijer, who helped chair the campaign.

While the foundation supported the strategic vision of continued urban growth in downtown Grand Rapids, it never took its eye off the lakeshore. In 1998, the university began holding classes at a new center in Holland. It provided lakeshore residents with more convenient access to higher education.

With campuses in Allendale, Grand Rapids, and Holland, Grand Valley continued to pay attention to the growing needs of the region. Toward the end of the 1990s, the university and foundation leaders saw another opportunity and a need they could help fill. As the life sciences sector of the local economy grew, the area’s hospitals and medical offices required more nurses, physician assistants, and other health care professionals. Grand Valley needed to expand many of its health science degree and program offerings in nursing, health care education, and physical therapy.

Grand Valley’s need for physical space also continued to grow. Grand Valley’s vision to fulfill these needs would be made manifest in the next decade.

In 1999, the foundation took another step to strengthen development for its future. It named Maribeth Wardrop, as Grand Valley State University’s first female vice president and the foundation’s executive director.

By decade’s end, the university endowment had grown to nearly $40 million, more than four times its size a decade earlier. And, thanks to the community’s continual support of the foundation, the university had opened in downtown the Richard M. DeVos Center, the Peter F. Secchia Hall, and the Fred M. Keller Engineering Laboratories. Those buildings joined the Eberhard Center and Meijer Public Broadcast Center as part of the Robert C. Pew Campus in downtown Grand Rapids. Bob Pew credited the community with making the downtown expansion a success.

“I think you’re in a wonderful community here, a community that’s done a lot to change in the past 50-60 years,” Pew said. “You could never do that in a lot of places… And I think it will go on.”

And the work continues.

As the new millennium arrived, physical evidence of the Grand Valley University Foundation’s success and the generosity of its members and the West Michigan community was everywhere.

On the Robert C. Pew Campus in downtown Grand Rapids, the Innovation Connection campaign was raising funds to build the John C. Kennedy Hall of Engineering to complement the Fred M. Keller Engineering labs. The Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences campaign was about to begin.

Foundation Chair Rich DeVos proudly announced at the foundation’s 2000 annual meeting, “Health is the new frontier.” In 2001, the foundation put a plan in motion to raise $21 million to support a health sciences center through its Building for Life campaign. Ground was broken in the spring for the Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences to be located on the Grand Rapids Medical Mile.

Impressive as these structures would be, the foundation and university leaders understood that what went on inside was far more significant.

“This campaign is about more than bricks and mortar,” said Grand Valley’s President Mark Murray, who succeeded Lubbers in 2001, during an annual foundation luncheon. “It’s about academic programs and opportunity…Private funding will help us focus on academic programs that will meet the long-term goals of the university, thereby increasing not only student retention rates, but also the quality of education our students receive.”

Given this focus, much of the foundation’s efforts went into supporting academic programs through a growing number of scholarships, endowed chairs, and centers of excellence. The Hauenstein Center for Presidential Studies, named for philanthropist Ralph Hauenstein, sponsored lectures and taught students leadership skills. The Sylvia and Richard Kaufman Interfaith Institute, established to promote understanding and tolerance among different religions, was another center for excellence.

The foundation initiated in 2005 another campaign to build a $5 million endowment for the Dorothy A. Johnson Center for Philanthropy and Nonprofit Leadership, a highly regarded program designed to educate and provide research in the areas of philanthropy and nonprofit management as well as to build pathways to public service.

In 2003, after more than three decades of supporting the university in countless ways, DeVos assumed a new position as the foundation’s general chair. Jim and Donna Brooks, both long-time supporters, began serving as the foundation’s vice chairs.

The university had become a living, thriving institution with a growing number of its students entering a rapidly-changing world. By 2007, the university’s endowment, thanks to the foundation members’ unwavering support, had become the seventh largest among Michigan’s 15 public universities. In that same time frame, state appropriations to Grand Valley had dropped to less than 20 percent of total revenues.

Under the guidance of foundation Vice Chairs Jim and Donna Brooks, the foundation kicked off its first comprehensive, multi-year campaign called Shaping Our Future.

Daniel and Pamella DeVos agreed to co-chair the Shaping our Future campaign with Jim and Donna Brooks. The campaign’s priorities would be to deliver nationally ranked programs to students in Michigan, support and help transform the region’s economy, and foster civic engagement through scholarships, academic programs, and capital projects.

One of the most notable facility needs was for a new library. The Zumberge Library was built in 1969 to serve a student body of 5,000, merely one-fifth the university’s 2010 enrollment. In September 2010, the university broke ground for the Mary Idema Pew Library Learning and Information Commons on its Allendale campus.

By decade’s end, the Shaping our Future campaign’s original $50 million goal was increased to a stretch goal of $75 million with the addition of the L. William Seidman Center, scheduled to open in 2013, for the business college at the Pew Grand Rapids campus. The center would honor the late L. William Seidman, one of the university’s founders, who died in 2009. Doug DeVos and David Frey agreed to co-chair the campaign, with Rich DeVos as honorary chair.

Throughout this time of much growth and many changes at Grand Valley, the one constant was the abiding support of the community and the foundation directors who continued to encourage the university to think forward and keep building for the future.

The next decade began as a time of celebration and transition for the foundation. In 2011, the foundation announced that not only did it meet the stretch goal of $75 million for the Shaping Our Future campaign, it exceeded it. Thanks to more than 17,000 donors, the foundation raised $96.4 million. The success of this historical first comprehensive campaign was a testimony to the strength and maturity of the foundation as it reached the half-century mark in 2015.

In the first few years of the decade, construction began on the Mary Idema Pew Library Learning and Information Commons and the L. William Seidman Center, which were both dedicated with much celebration by the Grand Valley community and the foundation in the Fall of 2013. The Robert B. Annis Field Station was completed that same year and significantly increased research capabilities at the Robert B. Annis Water Resources Institute in Muskegon.

In 2013 the university purchased 11 acres in downtown Grand Rapids across Interstate 196 from the Cook-DeVos Center for Health Sciences marking the first step in the expansion of Grand Valley’s Health Campus.

The Laker Effect campaign was announced in 2016 to raise money for students to start, stay, and succeed at Grand Valley. The campaign had ambitious goals for scholarships, student success programs, and academic excellence. When it was completed in 2020, the campaign exceeded its’ original goal of $85 million and set a new record for Grand Valley’s comprehensive campaigns at $132 million, thanks to 35,000 donors.

The Laker Effect campaign included construction of two new buildings on the university’s Health Campus, Raleigh J. Finkelstein Hall and the Daniel and Pamella DeVos Center for Interprofessional Health. Once completed, the Health Campus expansion significantly increased capacity for students and new programs in the health sciences. The campaign also included the Innovation Design Center for Engineering, the Jamie Hosford Football Center, P. Douglas Kindschi Hall, and the renovation of the Tom and Marica Haas Center for Performing Arts with its’ Linn Maxwell Keller Black Box Theatre, the Don and Nancy Lubbers Student Services Center, and The Blue Connection. Donor-funded scholarships rose to 550 and the number of endowed and named faculty positions doubled.

As the decade drew to a close, the foundation had helped create a Laker Effect that would last for generations, and the university began charting a course for the future. Grand Valley was now under the leadership of its’ fifth president, Philomena V. Mantella. It was an unprecedented time with major transformations in higher education. The GVU Foundation held its’ first virtual meetings to prepare for whatever would come next. The foundation’s history of entrepreneurial spirit and innovation will serve it well as the university embarks on what’s next for Grand Valley students and the West Michigan community.

1988 | L.V. Eberhard Center Grand Opening Thank You Video

The L.V. Eberhard Center was opened in 1988, thanks to the support of the Grand Rapids community and many private gifts.