News

Outreach, Diversity, and Art

January 31, 2020

Reprinted from the Society of Classical Studies.

Blog: Valuing Classical Translations for Outreach, Diversity, and Art

By Diane Rayor | Jan 31, 2019

Literary translation is a scholarly and a creative act in which a reader of the Greek or Latin becomes the writer for new readers. Like all readers, translators interpret the text, and in the field of classics, apply their scholarship and their poetic abilities to put the text into a modern language. Since many readers of our translations cannot read the original, they depend on us to transmit the voice of the original writer and to be transparent in our choices. By that I mean that the translator should proclaim whether the translation is aiming for accuracy (and what that means in particular), whether it adds or subtracts from the source text (such as Richmond Lattimore inserting his own lines into Sappho’s fragments), whether the work is an adaptation rather than a translation (clearly proclaimed in Luis Alfaro’s “Mojada: A Medea in Los Angelos”).

Diane Arnson Svarlien and I co-organized “A Century of Translating Poetry” (the first panel sponsored by the Committee on the Translation of Classical Authors). The panel had a good mix of scholars, including active translators (both organizers, Gonçalves, Hadas, and Wilson), two non-translators (graduate student Lee and Professor Vandiver), a poet (Hadas) and a performer of Latin poetry (Gonçalves). We had a lively discussion after the five talks with about forty audience members in a packed small room.

- “Exquisite classics in simple English prose”: Theory and Practice in the Poets’ Translation Series (1915-1920). Elizabeth Vandiver, Whitman College

- Quisque suos patimur manes: Trends in Literary Translation of the Classics. Rachel Hadas, Rutgers-Newark

- “Tools” of the Trade: Euphemism and Dysphemism in Modern English Translations of Catullus.Tori Lee, Duke University

- Performative Translations of Lucretius and Catullus. Rodrigo Tadeu Gonçalves, Federal University of Paraná, Brazil.

- Faithless: Gender bias and translating the classics. Emily Wilson, University of Pennsylvania.

As Susan Bassnett says, “The translation effectively becomes the after-life of a text, a new ‘original’ in another language….as an act both of inter-cultural and inter-temporal communication.” (Translation Studies 2013: 10). My response on the panel included much of the following, which is my take on topics broached in the papers and the ensuing discussions on issues of literary translation in classics. These thoughts are my own and do not claim to represent the views of the panelists. I believe that the best of literary translation is based on scholarship and techne (art/skill/craft), and that although translators are frequently undervalued in the academy, our work is essential for classical outreach.

It seems to me that since translators interpret the text based on their own experience, interpretive choices and strategies derive partly from social identity, including gender, as well as research. A call for more literary translations by a more diverse population of translators could bring to light a greater variety of interpretations, perhaps echoing the way that a greater diversity of classicists enriches other forms of classical scholarship. Gender as part of the translator package was addressed in one paper and raised in the questions for another.

Most of the panelists noted the ways that contemporary events shape a translation and its reception. I was revising my translation of Hecuba in a production at the University of Colorado, Boulder, this fall during the Kavanaugh hearings, which shaped the language of Hecuba’s response to Odysseus that “Those in power should not abuse that power,” as well as Hecuba’s argument to Agamemnon against Polymestor’s lies (“If someone does evil, his words should be flawed /and not make a persuasive case for injustice”). My director specifically asked that I see where I could shade the language to resonate with current events.

Gonçalves and Lee demonstrated (in different ways) that translations vary based on the translators’ skopos—their goals and targeted audiences. Lee showed how modern English translations of Catullus create poetry either more or less profane than the originals to appeal to diverse audiences. Hadas noted that multiple translations of the same work (sometimes even by the same translator) each present differing interpretations and priorities. In the forty years I have been translating Sappho, my interpretations, contemporary poetics, and the Greek texts themselves have changed. Even where the original text doesn’t change through new finds, there is no final, definitive translation—as much as I’d like mine to be that!

Literary translation has historically been undervalued partly because classicists haven’t considered it serious scholarship. It’s true that some translators are not serious scholars and their poetry can be beautiful. Vandiver explained that the Imagists’ manifesto for Poets’ Translation Series claimed that only content, not form, is important, and they implied that content is easily transferable. To them, scholarship, which includes knowing the language, not only was unnecessary, but detrimental. To me, this helps explain the long popularity of Mary Barnard’s Imagist Sappho, mistranslations and all.

Classicists often undervalue translation due to a misunderstanding: It’s all too easy to imagine that literary translation simply conveys the content of the original into a new language, as if tracing paper would do the job. Some people continue to think that any old public domain translation is usable or good enough for students. A further misunderstanding unique to classics is conflating the pedagogical tool called “translation” in our language courses (used to show that the student can comprehend the Greek or Latin passage) with literary translation.

Hadas quoted from her father’s memoir, when the “traditional boundaries” of classical scholarship actively discouraged translation in the academy. Wilson mentioned that institutional bias against translation leads to it being the territory of people retired or independent from the university. Translation won’t get you the job or tenure. That certainly was my own experience on the market almost three decades ago. I was tenured in the English department based on my translations and teaching before I co-founded the Classics Department at GVSU. The bias against translation in classics has only recently and perhaps marginally shifted today.

Literary translation is and should be recognized as essential outreach for classical studies in academia. It is a central component of the reception of classical texts by classicists and non-classicists alike. In high school and college classical studies courses, most everyone teaches using translations. Good translations can attract students to Greek and Latin language. They can also attract new audiences to classics from beyond the academy and enrich our target languages. Gonçalves, for example, with colleagues and students in the band Pecora Loca, performs Catullus and Lucretius in Latin and Brazilian Portuguese (along with other languages) in bars (https://www.pecoraloca.com).

Performance emphasizes sound, rhythm, and “innovative metrical patterns…in dialogue with the source text and contemporary poetics.” My own Classics Department has partnered with theatre for performances of ancient drama, and our biannual Homerathon is a big draw in the university and community. This is the delicate balance of bringing audiences to the Greek or Latin—while also leading the original into its new home.

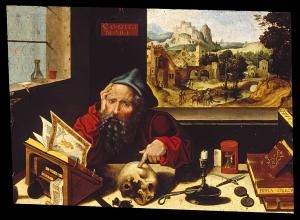

(Header Image: Pieter Coecke van Aelst, the elder (Flemish, 1502-1550). 'Saint Jerome in His Study,' ca. 1530. oil on panel. Walters Art Museum (37.256): Acquired by Henry Walters. Image via Wikimedia under Public Domain.)

Diane Rayor is Professor of Classics at Grand Valley State University, teaching Greek language, Classical literature, and mythology. She has published six translations of ancient Greek poetry and drama including Sappho (Cambridge) and Homeric Hymns (California). Euripides’ Helen and Hecuba will soon join her Medea and Antigone at Cambridge; all four were workshopped with their first casts.