Tim Evans peppers his presentations and conversations about botany with a folksy vibe, pop cultural references and even somersaulting, all to heighten interest in plants, a true passion for him.

He also is a meticulous scientist with an encyclopedic recall of plant species who is dedicated to working with students to help them not only learn about botany but also understand the research techniques necessary for working in a scientific field.

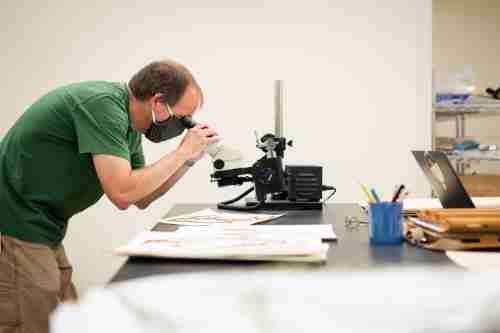

That attention to detail is evident in a storage room deep within the Kindschi Hall of Science. Evans, professor of biology, curates about 6,500 species of pressed plants for the Grand Valley herbarium.

He shares a flurry of information as he pulls files of pressed plants from a cabinet, quickly identifying what specimens represent distinctive characteristics of the collection, such as oldest or most unusual.

This appreciation for botany is not how Evans had envisioned his future. He entered his undergraduate studies as a pre-veterinarian student. During a biology class that studied both animals and plants, Evans realized his fascination actually was with vegetation.

“I switched to botany and never looked back,” Evans said.

The GVSU herbarium is one beneficiary of that discovered passion. Since his arrival in 2008, Evans has organized and digitized information about the specimens that he said can also be helpful for the larger herbaria collective network. For instance, the records in these research archives can help climate change researchers identify shifts over time in a plant’s flowering season.

Evans said all herbariums provide a long-term record of plants in a particular area. For Grand Valley’s, that means a strong representation of plants across Michigan as well as specimens from places such as Alaska and Puerto Rico for fellow Biology Department researchers.

He said he even has, under lock and key, a specimen of Phragmites (common name reed), which is a highly invasive species that has replaced most of the native population. To collect the specimen, he needed to obtain a permit as well as promise to secure it.

Having the plant on hand allows for molecular study, which fulfills a prime herbarium function, Evans said.

“Whenever we publish a research paper that includes molecular data, we need to have a voucher specimen deposited in a recognized herbarium to document the plant that the DNA was extracted from,” Evans said.

Tim Evans manages a collection of more than 6,500 species of pressed plants in the Grand Valley herbarium.

Another central purpose for the herbarium is as a teaching resource. Evans uses the herbarium for students in his systematic botany course, and said the archive helps students learn information about plants and how to use best research practices.

“I tell the students, ‘If you make a collection and you don’t get other information with it, such as the date, where it was collected and the habitat information for that specimen, science-wise, it has lost all of its value,’” Evans said.

Grady Zuiderveen, ’09, a botanist with the U.S. Forest Service, recalls the rigor of that course. He also noted the dedication Evans shows to students helped make the hard work worth it.

“I was always taught not to pass up a good opportunity, and I feel like Tim gave me that first opportunity when it comes to plants,” Zuiderveen said.

He said his deep research experience with Evans started as a first-year undergraduate. Along the way, a book recommendation from Evans about ethnobotany led to Zuiderveen’s own “aha” moment for his career. Zuiderveen also fondly recalled Evans’ endearing personality and how he wove moments of whimsy into his plant presentations.

Now, about the somersaulting.

Evans has recorded YouTube videos about botany that showcase both his passion for plants and his passion for fun. He even depicts a Rambo-like character with a necktie wrapped around his head. Who somersaults on a sidewalk. And does a kick jump before a lesson on poison ivy.

Evans calls Tradescantia (common name spiderwort) beautiful, in particular because of its flower.

His enthusiasm is infectious, never more so than when he talks about his all-time favorite plant: Tradescantia (common name spiderwort), which is from a plant family he has researched extensively.

Not what you expected?

He gets it.

“That genus is beautiful. It has bright deep blue to pink or violet flowers,” Evans said. “Some are weedy. Some people hate them because they can be pretty aggressive, but I think they’re beautiful.”

As it turns out, his holy grail is a plant from that family. Tradescantia bracteata is a species he knows from the state of Wyoming, and he also learned it was collected in Allegan County in 1938.

The scientist in him knows it is considered locally extinct. But the plant enthusiast in him often wins out, and he will find himself in late spring driving around places he would expect it to grow.

“I can’t get it out of my mind,” Evans said. “I have to find it.”