When a research team led by GVSU researcher Ian Winkelstern rented a pontoon boat near North Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, the operators of the rental business started advising on what islands to visit for a day of frivolity.

To their surprise, Winkelstern said: “Actually, we’re going the other way.”

“The other way” on the Intercoastal Waterway, a canal that runs from Florida to Maine, is not exactly welcoming to most people, said Winkelstern, affiliate professor of geology.

But for a geology research team searching for shells, sediment and other clues to learn more about what the conditions were like about 125,000 years ago, the last time the Earth was in the range of warmth it is now, going that direction revealed a treasure trove.

Research team members, including GVSU students, visited South Carolina in the summer as part of a National Science Foundation grant to study climate change by examining warm climates in the geologic past.

The study is being done in collaboration with researchers from the University of Michigan to study fossils from areas along the East Coast, Bermuda and the Bahamas. The combined award for the collaborative grant is nearly $450,000.

At the core of this study is trying to understand how oceans behave when the Earth is warmer, since ocean currents play a big role in regulating climate and moving heat around the planet, Winkelstern said.

“How the ocean current operates in a warmer climate tells you how life is going to be on the East Coast and Europe,” Winkelstern said.

Why travel to this part of South Carolina? Because it is about 1,000 miles due west of Bermuda, which is also part of the study. And South Carolina is on the other side of the Gulf Stream, the warm Atlantic Ocean current that causes Bermuda to be 10 degrees warmer than South Carolina in the winter, Winkelstern said. The Gulf Stream’s prominence in affecting climate makes it an important focus in this kind of research.

“With geological field work you picture the Rocky Mountains or the Grand Canyon, and with this we were in spider-infested drainage ditches in South Carolina...”

IAN WINKELSTERN, AFFILIATE PROFESSOR OF GEOLOGY

During the period they are studying, the sea level was much higher than now, Winkelstern said. Much of the Greenland ice shelf had melted and Antarctica was partially melted, circumstances that can affect ocean currents — including the Gulf Stream — by introducing an influx of fresh water, he said.

To carry out the South Carolina portion of the study, the researchers sought a location that was once under water but close enough to today’s sea level to collect the shells, coral and other materials that had once been submerged and now potentially hold interesting information for scientists, Winkelstern said.

“We needed to be within 15 feet of elevation of the current beach, not far from the actual ocean,” he said.

The work will hopefully help give insight into another core question for these researchers, Winkelstern said: “If the world is warm, what does raising the temperature 2 or 3 degrees mean for the Earth?”

Temperature records only date back to the 1800s, he said. That’s why researchers are interested in the oysters, clams and coral found in South Carolina drainage ditches.

“The most fun part about geology is getting your hands dirty, and digging in the dirt and finding fossils was all part of the adventure.”

GRETCHEN ANDERSON, GEOLOGY MAJOR

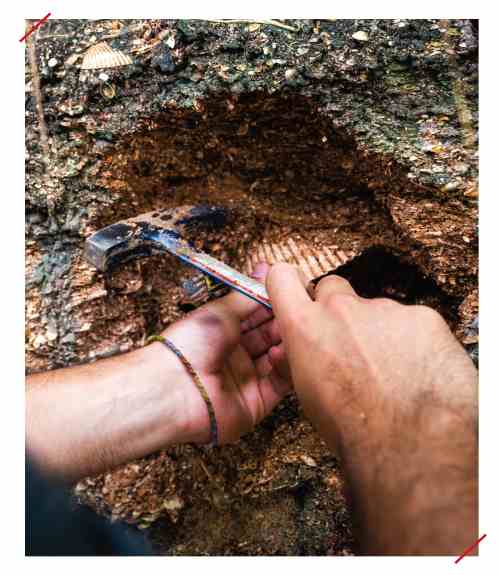

Ian Winkelstern, pictured at left, and his team unearthed about 300 fossils during their trip; keeping meticulous notes was part of the research process.

Unearthing clues to the past

When it comes to geology, it’s helpful to remember that references about how long ago a time period was are relative. Experts in the field can work with fossils that are tens of millions of years old.

So in geologic terms, the fossils found on this trip were from a recent time period and were fairly well preserved, Winkelstern said. Understanding their chemistry is the ultimate goal.

“Studying the chemistry of the shell itself tells you something about the water they grew in,” Winkelstern said.

A line in a shell represents growth, similar to the rings of trees, he said. Scientists will extract carbonite from each stage of growth. Winkelstern anticipates in some cases being able to decipher differences between summer and winter conditions in shells that had about a 15-year life cycle.

The researchers collected between 200 and 300 fossils, including shells of clams, the kind contained in clam chowder, that are smaller now but in that time period were the size of dinner plates, Winkelstern said.

It was challenging field work at times, he said. The team worked in ditches below a bluff near the tarmac for the airport servicing North Myrtle Beach, with steady traffic from planes carrying advertising banners over busy Myrtle Beach.

He acknowledged the setting may not be what people envision about geologists in the field.

“With geological field work you picture the Rocky Mountains or the Grand Canyon, and with this we were in spider-infested drainage ditches in South Carolina when it was hot and humid,” said Winkelstern, who added the spiders are common and not actually dangerous. “But they look terrifying.”

Students who were part of the research said the setting was fine by them. They said they were glad to conduct field work, especially in support of such an important project.

Above, the group travels on an outing to scout spots along the Intercoastal Waterway that were reachable by foot and presented good opportunities to look for fossils.

“Any opportunity to get out in the field, especially out of state, was great,” said Gretchen Anderson, who is majoring in geology with an environmental emphasis. “The most fun part about geology is getting your hands dirty, and digging in the dirt and finding fossils was all part of the adventure.”

Anderson has been working closely with the samples, scrubbing them with a toothbrush and doing other cleaning while also organizing them.

Lillian Minnebo, a geology major, said she was glad to have a chance to conduct field work after a period when opportunities were thwarted because of the pandemic.

She said she enjoyed working with the fossils, helping her apply what she has learned, while gaining a deeper understanding of geology.

“One of the things I’m passionate about is climate change, and the fossil aspect of how we’re learning from the past is fascinating,” Minnebo said. “It gave me a lot more perspective.”

Perspective is important while working with such a pressing issue as climate change, Winkelstern said. While there have been warmer periods on Earth, the pace of change for this warming is alarmingly fast when viewed through a geologic lens, he said.

He is dedicated to continuing to see how he can help address these concerns through geology research. As a student, he originally thought he wanted to specialize as a vertebrate paleontologist, but then gravitated to a field he thought was more practical and applicable.

“I’m hooked by this basic idea that you can reconstruct such a specific and short period of time from such a long time ago,” Winkelstern said. “It’s hard to extrapolate out, but it’s interesting that this work captures a snapshot of what it would have felt like to live on the East Coast at that time.”

He added that this work is the natural evolution of geology as a field.

“Geoscientists are working on environmental problems and solutions-oriented earth science, built on the backs of the geology that was done before,” he said.