Interfaith Insight - 2024

Permanent link for "Interfaith, Truth, and Social Justice," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 19, 2024

Originally published May 10, 2018

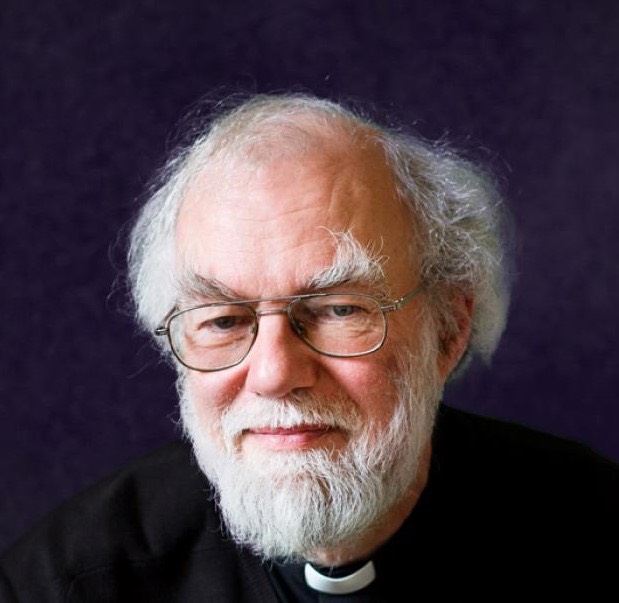

One of the persons I look forward to seeing and hearing in Cambridge is the former Archbishop of Canterbury, the Rev. Rowan Williams. Author of over 35 books, Lord Williams is also an academic and is currently the Master of Magdalene College. He spoke this week at the Woolf Institute on the topic, “The Importance of Interfaith for Social Justice,” and preached the sermon at Evensong at Magdalene College this past Sunday.

Most crises are not local. In the environment, political world, economic, or health arenas, issues cross national and faith community lines. Hence, our response cannot just be local. Underlying each of these concerns is the question, “What is it to be fully human?” Williams spoke directly about this in terms of the migrant issue in the United Kingdom. What do we owe to another person as a human being, but not necessarily a citizen? The faith communities must respond together on these issues.

Williams spoke of a common crisis that creates a common challenge, which must be met with common compassion. When the faith communities go beyond understanding and dialogue to working together for the common good, then action becomes the face of the interfaith efforts. He also turned the title around to explore “The Importance of Social Justice to Interfaith.” When we see someone who is “the other” involved in acts of generosity and compassion, we see the humanity in them and appreciate the depth of human character. It is a transformation in our “looking.”

He referred to the great American Catholic social activist Dorothy Day as one who lived her faith through her action in caring for the poor. He called it a “healthy counter to too much theology.”

In his book, Faith in the Public Square , Williams discusses the related issue of religious diversity and social unity. Does working together for the common good imply that we ignore our differences? Do we give up our truth claims in order to accept those who believe differently? He is critical of what he calls the “hopeful fantasy” that talking about truth is less important than talking about social harmony and justice.

Williams argues that the disagreement about truth among faith communities is actually very important to our common life. In the absence of making truth claims we leave open the door for power to have the last word. When we make claims for transcendent values, we must recognize that others also make such claims.

Williams writes, “What is needed for our convictions to flourish is bound up with what is needed for the convictions of other groups to flourish. We learn that we can best defend ourselves by defending others. … Christians secure their religious liberty by advocacy for the liberty of Muslims or Jews to have the same right to be heard.”

Thus our mission is not to give up our truth claims in order to seek justice, but to work with others “in finding what sort of values and priorities can claim the widest ownership.”

It is also a recognition that for most of our history the values of society have been shaped by religious belief. As Williams put it, “Diversity of faith points us towards a past in which there is a kaleidoscope of human perceptions, sometimes interacting fruitfully, sometimes in profound tension. … Religious diversity becomes a stimulus to find what it is that can be brought together in constructing a new and more inclusive history.”

This is true not only among religious traditions, but also within any particular community. We grow not by having everybody be alike, but by learning from each other. Whether it be in a denomination, a congregation, a family, or even a business, it is diversity that brings growth and new insight.

Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, previous chief rabbi for Great Britain, expressed this well in his influential book, The Dignity of Difference . Earlier solutions to difference led to crusades and the religious wars between Catholics and Protestants in the 1700s. Seeking to assert or defend a particular religious position through violence is also behind many of the terrorist acts of today.

Why do some people hate the ways that others worship God? Perhaps our concept of God is too small. If we took God seriously, Sacks suggests, we might see that God is bigger than our religions. He warns, “In a century when our powers of destruction have grown so great, either we live together or, God forbid, we die together.”

Religion must be a part of the solution, or it will continue to be a significant part of the problem. Williams again warns against the “compromise of fundamental beliefs or that the issue of truth is a matter of indifference. … But there is a proper humility which, even as we proclaim our conviction of truth … obliges us to acknowledge with respect the depth and richness of another’s devotion and obedience to what they have received as truth.”

In this attitude of respect, we recognize that “none of us have received the whole truth as God knows it; we all have things to learn.” Furthermore, our passionate beliefs as Christians, Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Buddhist, Sikhs or whatever else, are received as a gift not an accomplishment.

Affirming truth in a spirit of humility enables us to respect that others also affirm truth. Through dialogue and by working together we can find ways to support the common good and resist recourse to power and violence. It is in this way that we expand our understanding of God’s truth and work together for social justice and peace.