Interfaith Insight - 2024

Permanent link for "Seeing Others As Persons With Ultimate Worth," by Douglas Kindschi, Founding Director of the Kaufman Interfaith Institute, GVSU on February 26, 2024

Originally published July 12, 2018

The Rev. Dr. Rowan Williams for 10 years served as the Archbishop of Canterbury and head of the worldwide Anglican community. He is now the master of Magdalene College at Cambridge University and someone I look forward to hearing and speaking with each time I return. His latest book, Being Human ,” explores what it means to be human in terms of body, mind, and personhood.

In his chapter, “What is a person?” he makes the distinction between being an individual and being a person. Anything can be an individual instance of a certain category of things. I have a Model T and it is an example of something called an antique car. I can list the characteristics that establish it as a car and as an antique. There are distinctions between antique and vintage cars, or classic cars. The various states define antique differently when one is seeking an antique or historical car registration or license plate.

But when it comes to being a person, is there a checklist that one can list to determine whether one is a person, or is there something irreducible about being aperson? For Williams, description doesn’t work. We must go beyond the bundle of facts to define what it means to be a person. He writes:

“We can never say, for example, that such and such a person has the full set of required characteristics for being a human person and therefore deserves our respect, and that such and such another individual doesn’t have the full set and therefore doesn’t deserve our respect.” There is something irreducible, not just a fact about me, but “something mysterious, something not open to third-person analysis.”

The key is relationship, Williams argues. “We sense that our environment is created by a relation with other persons, we create an environment for them, and in that exchange – that mutuality – we discover what ‘person’ means.”

For Williams this has a profound religious basis, the assumption that “before anything or anyone is in relation with anything or anyone else, it’s in relation to God.” Thus, “when I look around, my neighbor is also always somebody who is already in a relation with God before they’re in relation with me. That means that there’s a very serious limit on my freedom to make of my neighbor what I choose, because, to put it very bluntly, they don’t belong to me.”

Williams warns about the individualist approach that looks to the self as the center, and not the relationships. In our world today he sees “an evolution of an ‘uncooperative self’ – a self that assumes that what comes first is this isolated interior core which then negotiates its way around relations with others … away from a sense of belonging with each other and taking responsibility for each other.” Quoting the French writer Alexis de Tocqueville, he writes, “Each person, withdrawn into himself behaves as though he is a stranger to the destiny of all the others.”

If I take the individualist approach I am tempted to see others not as persons in their own right, already in relationship, but as objects to be used or useful to my individual ambitions or desires. One is then inclined to respect others only when they share the same characteristics as oneself. Do they look like me, talk like me, come from the same racial and socioeconomic status, worship like me? Can I tick off enough on my checklist to respect them as human, like me?

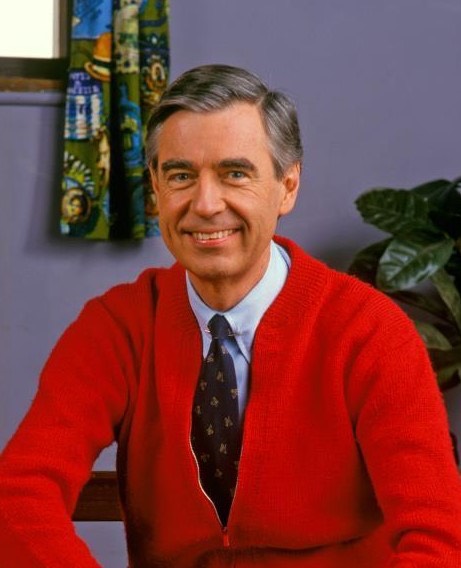

Returning from Cambridge, I’m struck by the interest in Mr. Rogers and his neighborhood. The documentary playing in theaters has generated multiple glowing reviews and essays. What is it about his story that draws our attention? I believe that in our individualistic, depersonalized climate, it is almost a revelation that there is another way to live. Rogers treated everybody, especially the children he spoke to and loved, as persons. They were not just individuals to be analyzed and checked off to determine if they merited respect. They were persons respected precisely because of their being – respected regardless of race, background, or physical limitations.

In a current essay, New York Times columnist David Brooks tells of a time when Fred Rogers met a 14-year-old boy who had cerebral palsy and asked the boy to pray for him. The boy, who had himself been prayed for many times, was shocked that Mr. Rogers requested his prayers. Later a reporter complimented Rogers on his clever way to boost the boy’s spirit by requesting that the boy pray for him. Rogers’ response was immediate. “Oh, heavens no, I didn’t ask him for his prayers for him; I asked for me. I asked him because I think that anyone who has gone through challenges like that must be very close to God. I asked him because I wanted his intercession.”

Brooks continues, “And here is the radicalism that infused that show: that the child is closer to God than the adult; that the sick are closer than the healthy; that the poor are closer than the rich and the marginalized closer than the celebrated.”

Rogers treated every person, every child with whom he interacted, as persons with inestimable value. Each person loved first by God deserved his love and respect as well. Let us follow his example and treat each person with the respect deserved, as one made in God’s image and loved first by God.