TWO-EYED

SEEING

Dig looks beyond history of logging town

to displaced peoples

TWO-EYED

SEEING

Dig looks beyond history of logging town

to displaced peoples

STORY BY PEG WEST

PHOTOS BY KENDRA STANLEY-MILLS

VIDEOS BY TONY PACKER

The towering oak tree commanded attention. So a group of students and faculty members who had been headed to an archaeological field school stopped to contemplate its place on the land as its branches and leaves soared overhead.

Set amid the ravines near the southern border of Grand Valley’s campus, the tree is estimated to be 350-400 years old. Rob Larson, an affiliate professor of natural resources management and a member of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, asked the group to consider all the tree has experienced.

“There’s so much more we can learn from these beings, even though they don’t speak and they don’t move the way we do,” Larson said. “Who would allow that tree to be cut down now?”

Larson then turned his attention to a sugar maple sapling sprouting just inches above the ground. It’s the kind of vegetation that is easy to walk through without a second thought. But Larson said it deserves the same respect that is afforded the majestic oak. Whether stories tall or inches tall, these trees are all an integral part of what he called Grandmother Earth.

With that perspective, he suggested, you’ll step around the saplings of the world.

STORY BY PEG WEST

PHOTOS BY KENDRA STANLEY-MILLS

VIDEOS BY TONY PACKER

The towering oak tree commanded attention. So a group of students and faculty members who had been headed to an archaeological field school stopped to contemplate its place on the land as its branches and leaves soared overhead.

Set amid the ravines near the southern border of Grand Valley’s campus, the tree is estimated to be 350-400 years old. Rob Larson, an affiliate professor of natural resources management and a member of the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, asked the group to consider all the tree has experienced.

“There’s so much more we can learn from these beings, even though they don’t speak and they don’t move the way we do,” Larson said. “Who would allow that tree to be cut down now?”

Larson then turned his attention to a sugar maple sapling sprouting just inches above the ground. It’s the kind of vegetation that is easy to walk through without a second thought. But Larson said it deserves the same respect that is afforded the majestic oak. Whether stories tall or inches tall, these trees are all an integral part of what he called Grandmother Earth.

With that perspective, he suggested, you’ll step around the saplings of the world.

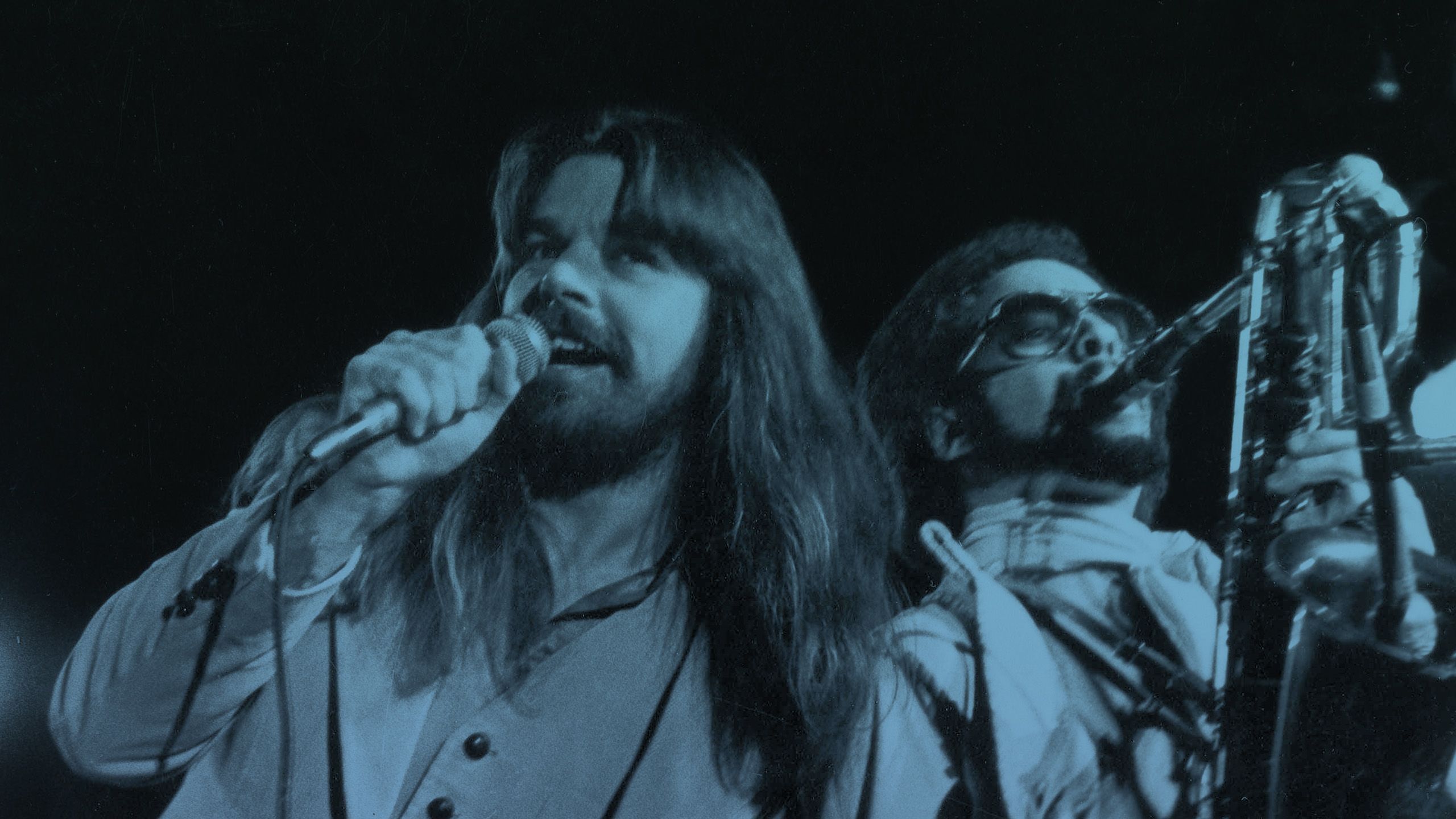

400-year-old oak

This oak tree stands near the site of where Blendon Landing once stood, just feet from an area where the rail line servicing the town ran. Experts believe the tree is 350-400 years old. That's easy to believe given the size of the trunk.

Branches thicker than the trunks of most neighboring trees curve skyward around those that are broken off. There are gouges and missing bark. And a full canopy of leaves. The scars are evident, but so is the resilience.

In its own way, this tree is communicating.

Two-Eyed Seeing

Looking at the species of a habitat as more than objects is an important component of the Two-Eyed Seeing approach, a way of looking at the world that is grounded in the traditions of Mi’kmaq, a Tribal Nation whose traditional territory, Mi’gma’gi, is located in what is now the Atlantic region of Canada. Variations of this approach are found in Tribal Nations across North America, also known as Turtle Island in many Indigenous cultures.

Two-Eyed Seeing involves using one eye to understand the strengths of Indigenous knowledge and the other to understand Western knowledge, then braiding those perspectives together for mutual benefit.

Larson imparted the tenets of that approach to students as part of a burgeoning partnership with Steven Dorland, assistant professor of anthropology, who led the field school efforts at the site of Blendon Landing, a logging town from the mid-1800s that once bustled along the Grand River near what is now the Allendale Campus.

For that partnership, Dorland, Wesley Jackson, assistant director of the field school, and other scholars worked to ensure they included an Indigenous perspective as they built upon research already done at the site.

“We wanted to tell the students, ‘Our focus doesn’t start with Blendon Landing and its features and artifacts; it starts with Indigenous peoples who were removed from the land, so that we can learn about the landscape and changing relations to the land,’” Dorland said.

Dorland connected with Larson through Lin Bardwell, assistant director of the Office of Multicultural Affairs, after he reached out to her to see how he could connect with members of the Indigenous communities.

To honor a true partnership, Dorland asked Larson how they could collaborate to ensure an Indigenous perspective and Larson’s interests were woven into the field school, rather than Dorland setting an agenda and seeing where Larson’s insights might fit in.

Larson’s response included a Two-Eyed Seeing approach and collaboration with Ali Locher, associate professor of natural resources management, to develop a plan to map the site, remove the invasive plants and analyze the human impact on the ecosystem around the site.

What that looked like in action was a true intersection of mindsets that recognized the original, displaced inhabitants of the land where Blendon Landing once stood.

At the dig site, some students worked to unearth artifacts such as nails, ceramics and pieces of glass to help tell the history of Blendon Landing. They incorporated techniques to minimize disruption to the land, such as working around tree roots to avoid cutting through them.

Emma Elliott, scrapes dirt from around tree roots during the field school. “It’s tiring but it makes me excited for the future,” Elliott said. “This is the career I want. It’s cool I get to experience it.”

Emma Elliott, scrapes dirt from around tree roots during the field school. “It’s tiring but it makes me excited for the future,” Elliott said. “This is the career I want. It’s cool I get to experience it.”

“It’s important to look past the historical site to see both sides of the story.”

Michelle Oberlin, Student

Michelle Oberlin jots down notes during the archaeological field school at Blendon Landing.

Michelle Oberlin jots down notes during the archaeological field school at Blendon Landing.

Students in Steven Dorland’s class hike to the field school at Blendon Landing with tools and equipment.

Students in Steven Dorland’s class hike to the field school at Blendon Landing with tools and equipment.

Cody Chapin, left, and Zoya Dean look at artifacts they found while digging during the field school.

Cody Chapin, left, and Zoya Dean look at artifacts they found while digging during the field school.

And in the nearby vegetation, another group of students focused on addressing dynamic changes of the landscape by identifying and removing the species that invaded the land that Indigenous peoples knew and restoring conditions for native plants to once again thrive.

Larson said foundational ecosystem members such as trillium and mayapples are engaged in a “silent battle” as they fight for space against invasives, including the garlic mustard, multiflora rose and autumn olive that the field school was primarily targeting.

Students at the dig site also addressed the dynamic changes of the landscape by removing species that invaded the land that Indigenous peoples knew and restoring conditions for native plants to thrive.

Students at the dig site also addressed the dynamic changes of the landscape by removing species that invaded the land that Indigenous peoples knew and restoring conditions for native plants to thrive.

“With a lot of invasives, their presence changes the ecology of a system,” noted Locher, the faculty member who partnered with Larson. “For example, autumn olive will actually change the nitrogen levels of the soil to promote their own growth but inhibit the growth of other native plants. So the invasives have a competitive advantage and it ends up being a monoculture.

“If you have natural native diversity, a system is more intact and stable than if you have invasives that outcompete the native communities and make habitat for themselves.”

Ultimate goal: a true connection

Two students who have studied anthropology at GVSU said the field school offered important insights.

“It’s very important to be a member of a community and we respect the fact that this land that we’re on was populated by Native Americans so many years ago,” said Andrea Vitales-Lanuza. “As far as my experience personally, I do have Native American ancestry, not from this area, from farther south, but it’s great to be able to reconnect with that aspect of who I am, even if it isn’t this particular area where my family is from.”

Added Michelle Oberlin, who is considering a career in archaeology: “It’s important to look past the historical site to see both sides of the story.”

For Larson, the power of connection is a recurring theme as he reflected on this work.

“Everything came from the land; there was this inherent connection. They couldn’t separate themselves from it,” Larson said. “That was our pharmacy, it was our grocery store. They depended on and were interconnected with every aspect of the ecosystems.”

The field school and the still-developing partnership represent efforts in the anthropology field to create a platform for inclusivity growth, particularly for Indigenous communities, Dorland said.

Larson said he is grateful for the connection with Dorland and how he has conveyed these philosophies to students. Larson is hopeful this interdisciplinary collaboration will help launch more opportunities for understanding and transformation.

“As long as there is an investment, relationships continue to grow,” Larson said. “It is my hope, working with Steven and possibly others on campus, to build a continuing collaboration based on mutual trust and respect that benefits the greater good, the campus community, our society as a whole and the good of our Grandmother Earth.”

‘The goal is to be as one’

On a warm day in the Arboretum, the setting and the message from visitors melded for students and faculty members associated with the archaeological field school.

Jonathan Rinehart, a two-time GVSU graduate and a behavioral health clinician for the Nottawaseppi Huron Band of the Potawatomi, along with his wife, Liz Rinehart, a visiting professor of early childhood education, hosted the gathering.

They were invited to speak by Steven Dorland, assistant professor of anthropology, as part of his effort to ensure the Indigenous perspective was woven into the field school. The Rineharts wanted to impart the importance of honoring the land, respecting different traditions, and recognizing that all living beings are here for a purpose.

“Each of us is a good being,” said Jonathan Rinehart, who earned both his bachelor’s degree and master’s degree in social work at Grand Valley.

They shared traditions such as creating small pouches filled with tobacco, which Jonathan said serves as “a sponge that gathers our thoughts and prayers.”

Later, as Liz discussed our connection to the land, she passed around a shallow wooden bowl containing strawberries and explained how special these berries — among the first to emerge during the growing season — are.

“The seeds are on the outside, which represents generosity,” she said. She encouraged those gathered to eat the whole strawberry out of respect, as even the green part that often goes uneaten is part of the fruit.

She told the group that strawberries are considered a heart berry in Anishinaabek (People of the Three Fires) lifeways.

“Food is medicine. Strawberries feed the heart,” Jonathan added.

Liz Rinehart ’19, left, offers strawberries to students like Erin Johnston, right, as she talks about her Native American culture.

Liz Rinehart ’19, left, offers strawberries to students like Erin Johnston, right, as she talks about her Native American culture.

He also shared his personal story of being a high school dropout who worked his way to earning both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees in his 40s. The average age to earn a degree in the Native American community is 41, he told the group.

Part of life’s journey is to find out what was made for us and finding the places where we are supposed to arrive, he said.

The Arboretum was the right setting for the gathering to help emphasize our connection to the land and the energy of the Earth, Jonathan said. We are all part of a time continuum, and “the goal is to be as one.”

MORE FROM THE SPRING 2024 ISSUE