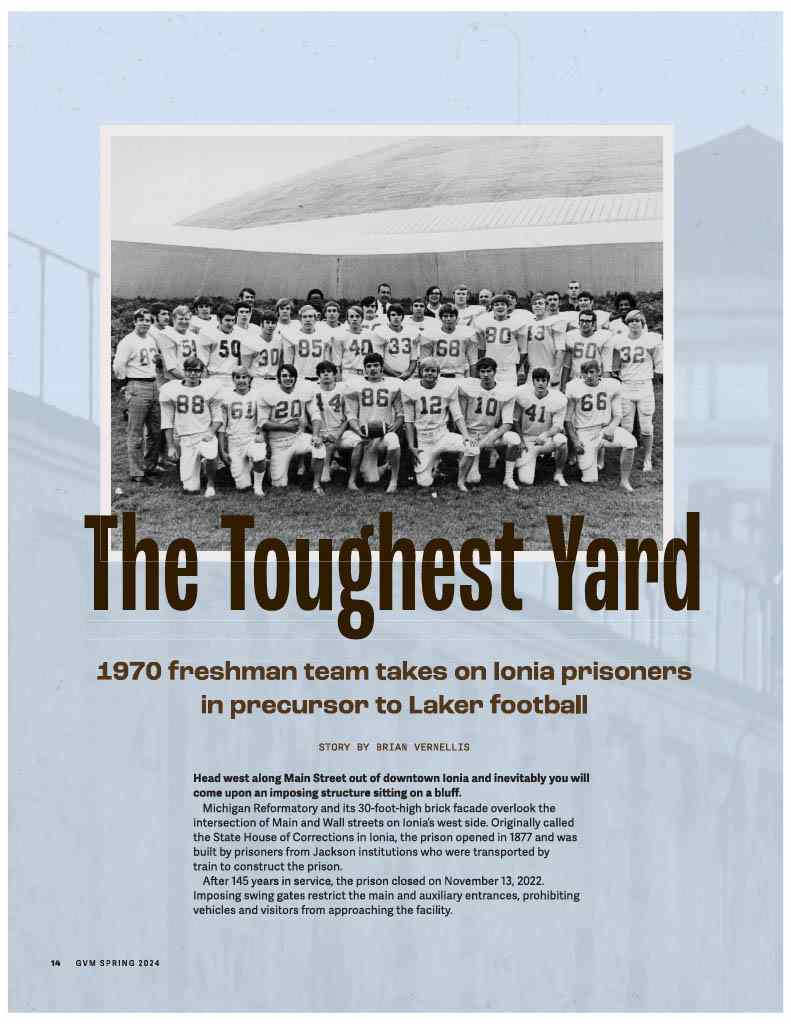

"The Toughest Yard"

Strapped for cash, Grand Valley State University's brand-new football squad in 1970 agreed to take on a team outside the typical rotation: players incarcerated at Michigan's oldest prison, the Michigan Reformatory.

As GVSU President Philomena Mantella wrote on behalf of this program, "removing obstacles to higher education is a tenet of our work at GVSU and we are proud of our success in increasing access for underserved populations. [...] As one of Michigan’s largest public universities, we are dedicated to serving the greater good and helping people from all across the state."

For far too long, incarcerated students have been effectively cut off from postsecondary education due to "tough on crime" policies that rendered them ineligible for federal student aid. Thanks to years of advocacy, that barrier has been removed, and it is now our duty to once again serve this community.

“In addition to the tutelage of experts and the benefit of diverse perspectives that a classroom provides, a college education is a pathway back into society.”

—

Alexander X, "Learning to Live"

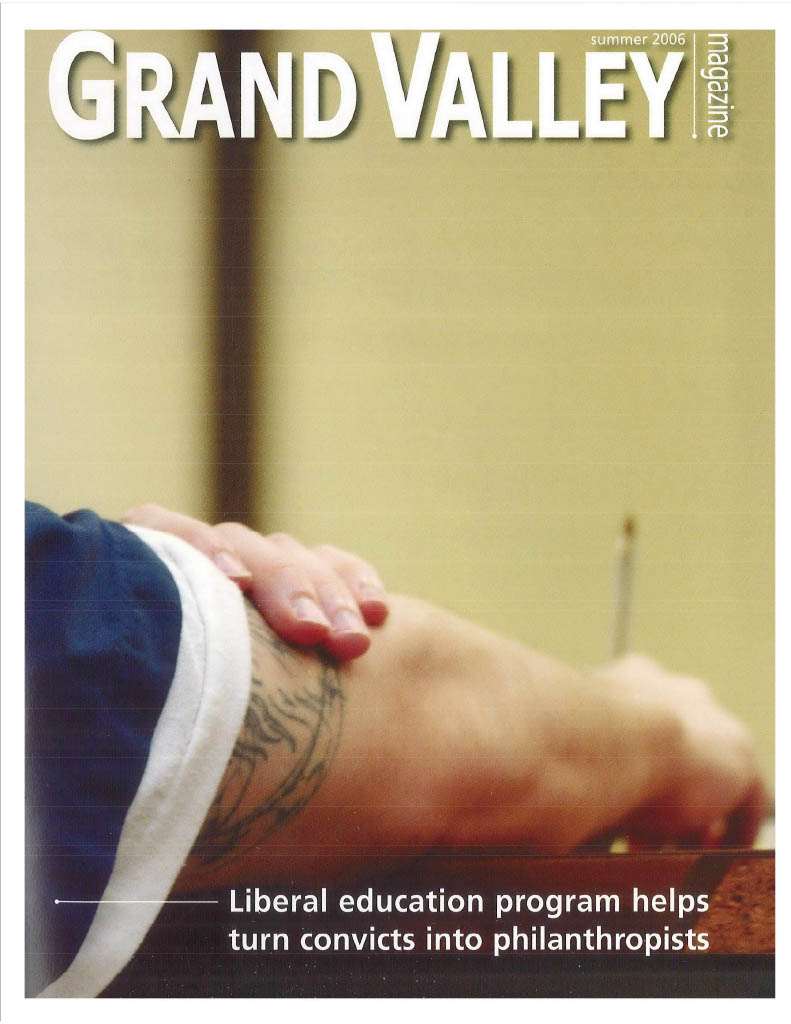

The Bellamy Creek Program actually continues and expands a longstanding tradition of prison-based education at Grand Valley State University.

In the mid-1990s, more than 90% of carceral systems across the country offered some postsecondary educational programming, enrolling nearly 40,000 students. As public sentiment embraced “tough on crime” policies, however, Congress rescinded Pell grant eligibility for incarcerated students in 1994. The proportion of enrolled incarcerated students plummeted in the years to come, and most colleges and universities fled the carceral system.

GVSU, on the other hand, found other ways to engage people behind bars.

Strapped for cash, Grand Valley State University's brand-new football squad in 1970 agreed to take on a team outside the typical rotation: players incarcerated at Michigan's oldest prison, the Michigan Reformatory.

From 1998 to 2011, Michael DeWilde, then a faculty member within the GVSU philosophy department, offered the Community Working Classics program at several Michigan prisons.

From 2009 until the prison closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, students from GVSU's "outside" campuses would travel to the Michigan Reformatory to take classes with "inside" students.

Our student voice council president said it best when he explained, "while we may be incarcerated at this moment, we are not inmates. Starting today we are now students, we are scholars and we are academics."

In the Bellamy Creek Program, we very intentionally do not use terms like "prisoner," "inmate," "felon," or "convict." As far as we are concerned, our students are just that: students.

We go a little farther than that, however — we'd like to see people reconsider the above terms in all circumstances, not just in the classroom. What we call someone both shapes and is shaped by how we see them. Here, we follow the pledge established by our colleagues in this field, the Formerly Incarcerated College Graduates Network. According to FICGN, "The vocabulary typically used to describe formerly incarcerated people has been largely influenced by media and popular culture, which often dehumanizes individuals by reducing them to their actions. Terms like 'suspects,' 'offenders,' 'predators,' and others strip individuals of their agency and humanity, functioning as titles that replace a person’s name or identity. This dehumanization perpetuates stigma and hinders reintegration." We strongly urge you to join their pledge and recognize humanity first and foremost.

Higher-education-in-prison (HEP) programs most often evaluate themselves by measurements valued by the carceral system. Traditionally, these measurements center on recidivism. Although the term's definition notoriously varies study to study, it fundamentally reflects the instance of committing a crime after release from prison. In HEP programs, for example, measuring recidivism usually means measuring the proportion of graduates who leave prison and then commit another crime that results in an additional prison sentence. Recent scholarly work has added some much-needed nuance to this measurement — taking into account the severity and/or frequency of subsequent crimes, for instance — but no matter the method, measuring recidivism is still measuring criminality.

This is certainly important for departments of correction when they weigh the value of permitting an HEP program to operate inside a prison instead of, say, an additional peer-support or financial literacy program. There is limited capacity for programming inside, both in terms of the physical space and the personnel required to monitor it, and departments rightly seek the programming that most effectively assists people in successfully returning to society. Many studies point to dramatically reduced recidivism rates for those who receive education while incarcerated. Perhaps none are so frequently cited as the groundbreaking 2013 RAND study that found incarcerated people "who participate in correctional education programs had a 43 percent lower odds of recidivating than those who did not." And "correctional education programs" here includes both postsecondary and secondary programs. Many studies that focus exclusively on HEP find much lower rates of recidivism among graduates.

But as an institution of higher education, we measure success differently.

We want to know how well we satisfy students' needs, such as by measuring student retention or getting their feedback on course content or instruction. We measure how engaged students are in extracurriculars, or how often they attend tutoring sessions. Above all, in the semesters to come, we hope to also measure our success by metrics that students themselves establish. After all, program evaluation is a key part of public and nonprofit administration -- the very field that students in the Bellamy Creek Program are studying. Please continue to watch this space for the ways students engage this discipline!